Today, 15 June, is the anniversary of the 1977 general election, the first elections held in Spain after the death of General Franco and an important landmark in the Transition which followed the Dictatorship. To mark this date IHR is publishing this review of a new book by Sebastiaan Faber, Professor of Hispanic Studies at Oberlin College, Ohio.

In recent years it has become commonplace to attribute many of the features of Spanish politics to the limitations of the Transition. Some people have called for reform of the 1978 Constitution and for a “Second Transition.” The exhumation of Franco’s corpse and its removal from the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen) in October 2019 briefly attracted the attention of the world’s media [See The people buried in the Valle de los Caídos: Where did they die? ]. Its symbolic significance is used as a starting point by Faber for a discussion on contemporary Spain and the influence of its troubled twentieth century past. This influence may be summed up in the words of the historian Jaume Claret:

“(S)peaking in general terms, we could say that for Spanish society – for Spanish democracy – the past is absent. In a sense it simply does not exist. And yet the weight of that absent past is undeniable” (p. 231)

The book is based on interviews conducted in 2019-2020 with a range of Spanish observers, most of them journalists and historians. Faber does not claim that his interviewees cover the diversity of Spanish opinion: he points out that most of the people involved “would identify as progressive rather than conservative” but defends this by adding that “the debate about the questions driving this book has been more intense and varied among the Left than on the Right” (p. 21). In fact, the different approaches and opinions of those interviewed make this a stimulating and thought-provoking discussion which should be of interest to readers in Spain as much as to those in the English-speaking world.

The legacies of both the Dictatorship and the Transition are discussed not only in institutional terms (such as the failure to reform either the judiciary or the universities) as well as in sociological terms.

Not all of those interviewed see these legacies as important. The journalist José Antonio Zarzalejos traces much of Spain’s current political polarisation to the refusal of the Partido Popular to accept defeat in the 2004 elections. (Perhaps it is worth noting that Vox – and, to a lesser degree, the Partido Popular – have been equally reluctant to accept the legitimacy of the current Socialist-led government). Another interviewee, the cultural critic Ignacio Echevarria, argues that the Francoist legacy has been exaggerated by politicians on the left for political purposes and attributes many of the features of modern Spain to her pattern of development stretching back over the past 200 years.

Despite the disagreements among the contributors, common themes emerge, among them the lack of institutional reform after the death of Franco. One of the consequences of this, according to the journalist Guillem Martinez, is “constitucionalismo” (“constitutionalism”) which he sees as a “reactionary interpretation” of the constitution which is used to defend the myths of both the Dictatorship and the Transition (p. 84).

The judge Joaquim Bosch emphasises the lack of judicial independence, which he attributes partly to the fact that judges know that promotion to the highest courts depends on them gaining the support of one of the two major political parties. Also untouched by the transition were the country’s universities, some of which have been affected by scandals in recent years: the historian Luis de Guezala contrasts the destruction of the higher education system in the Francoist purges after the Civil War with the lack of change in personnel after Franco’s death.

Several interviewees, including the journalist Cristina Fallarás, stress the way in which the major business corporations in Spain are descendants of companies which benefitted from the policies of the Franco Regime: its expropriations of the property of Republican supporters, its reliance on forced labour after the Civil War, its repression of the labour movement and the cosy relationship which large corporations enjoyed with the regime. One legacy of this which is outlined by several commentators is the influence of major corporations over many Spanish newspapers, to which should be added the power still exercised by Spanish governments over broadcasting.

Among the less obvious legacies of the Dictatorship which Faber identifies are many of the assumptions about democracy and the language in which politics is discussed: as he points out, many right wing politicians and their supporters still use language dating from the Dictatorship, referring, for example, to people on the left disparagingly as “reds”, while labelling supporters of Basque and Catalan independence as “separatists” or agents of “anti-Spain.” Guillem Martínez argues that the problem is not Francoism itself, but that Spain’s democratic culture has “normalised” Francoism so much that society is unaware of the influence of the dictatorship. Politics itself, he adds, was stigmatised and issues which are viewed as “political” are dismissed by many people as being unseemly and partisan.

At the same time it is clear, as many of the contributors argue, that important features attributed to the Dictatorship could be found in Spain long beforehand. The historian Ricard Vinyes points out Francoism merely inherited the most conservative and reactionary ideas and views from earlier periods. The legal historian Sebastian Martin agrees and identifies among these views a hierarchical view of society and a “uniform” and “imperial” view of Spain as a Catholic society. Emilio Silva, one of the founders of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (AHRM), is in agreement over this and adds that Francoism blocked – and is still blocking – the modernisation of the country.

There is almost universal agreement over the inadequacy of the teaching of Spanish history in schools and the urgent need for a greater and more informed coverage of Spain’s twentieth century past. Though the civil war and dictatorship are on the curriculum, they form the last part of an overcrowded programme, which means that they are often not covered at all, which is, perhaps, a relief to some teachers who regard these as politically sensitive topics. Many of the teachers themselves, however, are ill-trained for the task. Fernando Hernández Sánchez, who trains secondary school teachers, points out that the practice, inherited from the late Franco period, of teaching about the Civil War as a struggle between two “bandos” (“sides”), not only avoids mentioning the fact that the war started with a military revolt against a democratically elected government but also helps perpetuate a moral equivalence along the lines of “both sides were to blame” and “both sides committed atrocities.” He describes the population’s knowledge of the past as a “black hole” which, he argues, is growing in size. He points to this ignorance of the past as providing a fertile environment for the growth of right-wing myths.

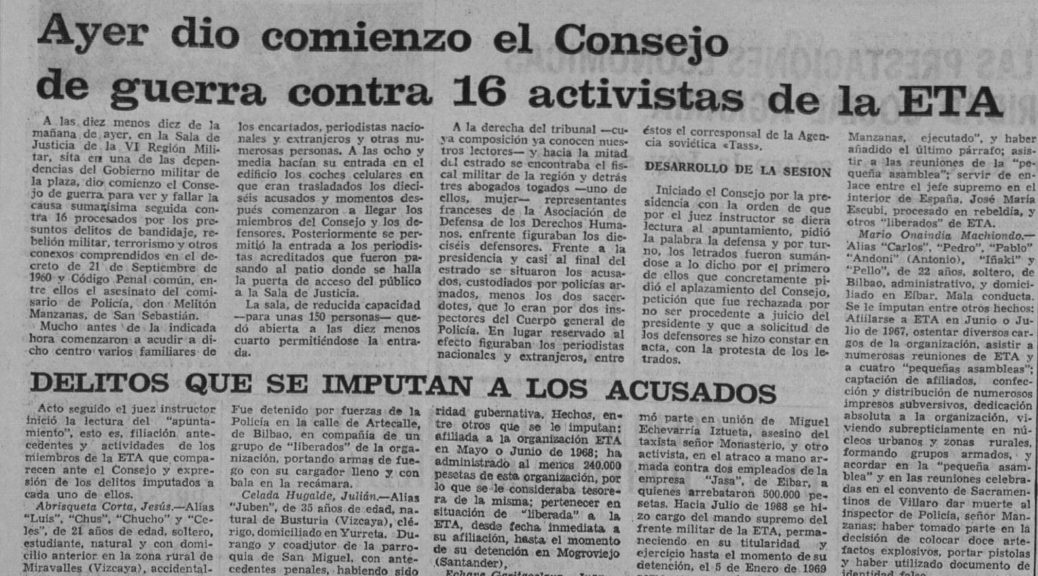

As might be expected a variety of other measures are advanced, though none of the contributors is optimistic about their chances of being adopted. Guillem Martínez calls for legislation forcing the courts to annul the sentences passed by the Franco dictatorship’s courts because these judgements express the idea that Francoism was a legitimate form of authority. He argues that the 2017 law passed by the Catalan Generalitat annulling Francoist sentences was “bogus” because the annulment of sentences is not the role of parliaments. Logically, any such annulment by the courts would raise the question of the seizure by the Dictatorship of the property of those who had supported the Republic [See Victims of Francoism in Catalonia, finally available on opendata].

Antonio Maestre calls for the revocation of the 1936 Decreto de Incautacion de Bienes Materiales (Decree-law to Seize Material Goods) which authorised such confiscation as well as for the repeal of the 1977 Amnesty Law.

It is difficult to do justice in a review to the range and complexity of the arguments introduced in this short book. In his conclusion Faber argues that, in some respects, Spain is not unique in facing these challenges. As he argues, many other countries, often seen in Spain as “normal”, also have problems dealing with their conflictive violent past, whether in relation to dictatorship, imperial rule or slavery. As he also points out, the populist right across the world wants to present history as something which should make citizens feel proud, by extolling “heroes” of the past. Vox is not unique in this, any more than it is novel in the Spanish context. These are good points and, although most readers will look to this book to help them to understand contemporary Spain, there is much here which should cause those from other countries to reflect on their own societies and the celebration of mythical versions of their own histories.

Sebastiaan Faber, Exhuming Franco: Spain’s Spanish Transition (Vanderbilt University Press, 2021)

A Spanish edition is planned for publication in 2022.