On 6 October 2017 Innovación y Derechos Humanos submitted a request to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Institutional Relations & Transparency (Departament d’Afers i Relacions Institucionals i Exteriors i Transparència – DRAEIT) asking for a copy of the Catalan Government’s census of people forcibly disappeared during the Spanish Civil War in order to include them in the central database which we are compiling of victims of the Civil War & the Franco Regime.

The Comission for the Rights of Access to Public Information (Comissió de Garantia del Dret d’Accés a la Informació Pública) which is the highest Catalan authority for access rights to information, has denied ihr.world access to the names of the people listed on the Generalitat de Catalunya’s census as having been forcibly “disappeared” during the Civil War.

The census data which the Generalitat is refusing to release was initiated by the Catalan Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (Asociación de Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica de Cataluña) and was then granted to the Generalitat. The Association still publishes on its website petitions from the relatives of victims of forced disappearance.

The Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances of the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights requested three years ago that the Spanish state should establish a centralized database of the victims of forced disappearance (further information aquí ) CHECK LINK.

From our point of view, in this particular case, the public interest in this information and the assistance that this may be to the families of the disappeared overrides the protection of personal data, especially since, in these cases, the majority disappeared between 1936 and 1939. This means that, for example, someone aged 16 in 1939 would now be 95 years old.

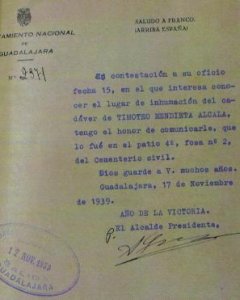

Moreover, there is a serious and absurd contradiction between, on the one hand, the Generalitat’s release to the public of the llista de reparació jurídica de víctimes del franquisme (a list of people granted judicial reparation by the Catalan government for sentences incurred under the Franco regime – which is included in our database), which lists the full names of people and covers the years 1939-1975 (the release of which, the Generalitat argues, is permitted by law) and, on the other hand, its refusal to make public the names listed in the census of victims who disappeared.

In November 2017, DRAEIT informed us that our request had been accepted and that the data had been published and could be downloaded via the open data gateway of the Generalitat. Even then, the data giving the first names and surnames of the disappeared had been replaced by their initials so that they could be used for research purposes in history, statistics, science and gender studies while respecting the rights of the families by not publishing sensitive information about their forebears.

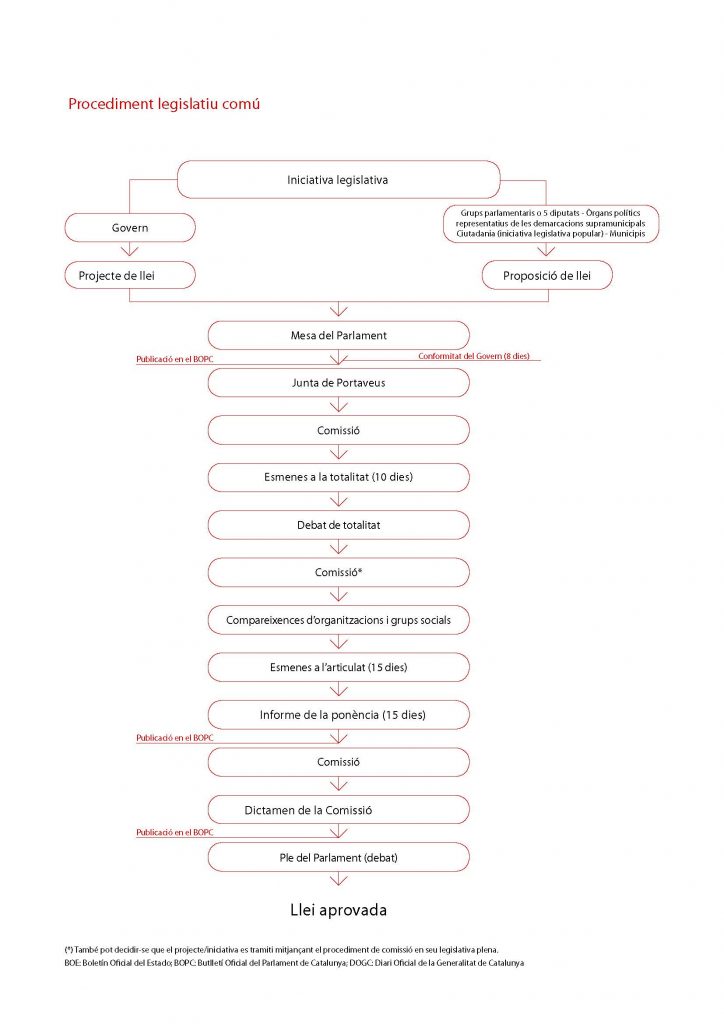

Faced with this response, we petitioned the GAIP (the commission which guarantees the right of access to public information) asking why the data supplied did not match that requested – in other words, why the first names and surnames of the people listed had been replaced by their initials.

GAIP asked for a report on our request from the Catalan Authority on Data Protection (Autoritat Catalana de Protecció de Dades or APDCAT)

The conclusion which was reached by the report by APDCAT (see the report (12 pages, single spaced) is that the Regulations do not prevent access to information about those people who have disappeared in cases where a judicial declaration of their death is also included in the case file of the Generalitat. However, in the cases of those disappeared people for whom there is no judicial declaration of death, the rules on data protection permit access only to the data disclosed, provided that this information does not permit their identification.

In the first place, according to APDCAT, access to the details of the identity of these disappeared victims is information which should be of interest to their families only. “The objective of locating and identifying these people is based on the need to recognize their dignity and on the rights of their families to obtain information about their fate”. APDCAT points out that the association has no connection with the families but requests access to the information about all of the people included in the database in line with the legislation on transparency.

In the first place, according to APDCAT, access to the details of the identity of these disappeared victims is information which should be of interest to their families only. “The objective of locating and identifying these people is based on the need to recognize their dignity and on the rights of their families to obtain information about their fate”. APDCAT points out that the association has no connection with the families but requests access to the information about all of the people included in the database in line with the legislation on transparency.

In the context of the investigation of the disappeared victims it is not possible to deny the interest of society in discovering the number of the disappeared, their origins and the circumstances in which they disappeared. This data is available to the general public via the open data portal and, according to APDCAT, should be sufficient “without unjustifiably sacrificing the privacy of the people who could be affected”.

On the other hand, the report is also based on the principal of the minimal presentation of data outlined in General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and European Council, which requires that “any required data processing, should be restricted to the minimum data necessary for the purpose”

Secondly, with reference to the case for providing access for relatives to this information, the DRAEIT has responded by arguing that relatives already have access to the data base. “It is clear that access to the information requested does not appear justified in order for the victims’ families to obtain information which they already have or which they may obtain by means of channels expressly provided for them to access information held by the Administration.”

Finally APDCAT states that it does not recognize ihr.world as researchers and considers that access to this data cannot be provided wholesale and that its release should be evaluated on a case by case basis. “It is necessary to take into account that information relating to the circumstances of the disappearance of people during the Civil War and the ensuing period of Francoist repression is information of a sensitive character and divulging the identities of those affected implies interference not only in the privacy of the disappeared person him or herself but also in that of their family descendents”. ¡This argument is precisely why it was necessary to pass a law in order to facilitate the release of the list of llista de reparació jurídica de víctimes del franquisme! (see above for details)

As a result of the report from APDCAT of March 2018, GAIP (which, you may recall, is the commission for the rights of access to public information, with all of the responsibilities which this involves) issued a report (15 pages single spaced) in which they refuse to allow access to the information requested.