In 2010 the Guadalajara branch of the Izquierda Unida party published a list of the hundreds of victims of the Francoist repression in the province.The list included the names of 839 people who were shot. Of these 217 were executed in the city of Guadalajara itself: 69 of these were natives of the province and the remaining 148 came from other provinces. Ihr.world aims to use documents such as this list, wherever possible supported by references to the archives, to create a central database of the victims of the Civil War and the subsequent Franco regime.

At the age of thirteen Ascensión Mendieta, the daughter of one of the men on this list, opened the door of her home because someone was knocking. A group of men took her father away and executed him. She never saw him again and has spent her life taking flowers to the city cemetery, knowing that her father’s body had been thrown into a mass grave there. Since 2013 she has been fighting to recover the remains of her father; her efforts have finally been successful.

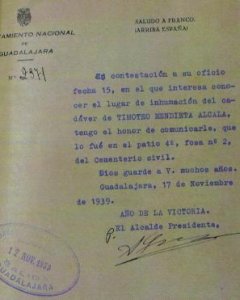

Timoteo Mendieta, who worked as a butcher, was shot on 15 November 1939 after being tried by a court martial on charges of having belonged to the Socialist UGT trade union and of having been ‘an accomplice to rebellion’. He left behind a widow and seven children. Later a wall was built in the cemetery to prevent families such as the Mendietas gaining access to the mass grave. This wall was only demolished in 1979, four years after the death of Franco.

The Spanish justice system refused to allow Ascensión Mendieta to exhume her father’s corpse. Blocked in this way, she flew to Buenos Aires, celebrating her 88th birthday on the flight, to testify before the Argentine judge María Servini in what has become known as the “Argentine lawsuit”.

As a result of this, Ascensión Mendieta has become the first descendent of a victim of execution by the Francoist state to gain the right to exhume the remains of one of their relatives. For the first time also the descendent of such a victim has been able prove before a judicial system (in this case an Argentine court under universal justice) using documentary evidence – as opposed to DNA evidence – what happened to him, that he was executed, thrown into a mass grave and that his relatives were prevented from gaining access to his remains. Such cases are not permitted in Spain as a result of the 1977 Amnesty Law. In the words of the lawyer Ana Messuti, interviewed on SER radio, the role of the courts in Guadalajara in accepting the ruling of the Argentine judge has been of fundamental importance.

Few Spanish media outlets have followed this story. Among those which have are the TV channel La Sexta and the newspapers, Público and eldiario.es:

For photos relating to this case go to flickr of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH) . The association financed the two exhumations in Guadalajara cemetery: in grave no. 1 in January 2016, which proved negative, and in grave no. 2, last May, which proved positive. There is also a photo of the chief Justice of Guadalajara greeting Ascensión Mendieta.

ARMH is a non-governmental organisation which receives no state support. The most important contribution for this exhumation was provided by an electricians’ union from Norway which since 2014 has donated 50,000 euros.