Last year we published a selection of books dealing with aspects of the Civil War and the Franco Regime. We continued this this year with some Some Recommendations for Summer Reading Following on from this previous post (1) New Books , today we discuss (2) Memoirs of the Civil War and the Post-War period by female writers. In relation to this you may also be interested in looking at our virtual exhibition Summary Military Proceedings against Women . Another article will follow about (3) Forced Labour in Franco’s regime.

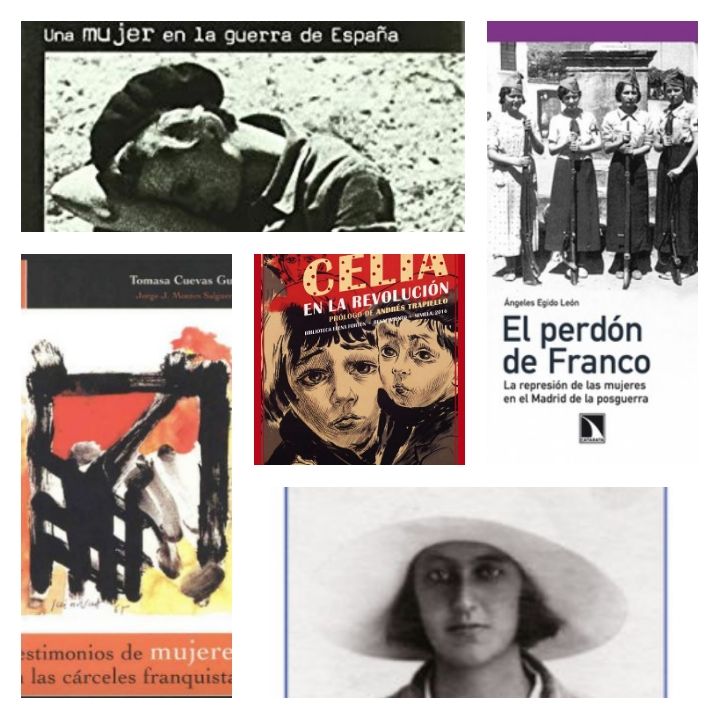

- The first person to reveal to the outside world the nature of the repression which occurred in women’s prisons during the Franco Period was, without any doubt, Tomasa Cuevas. Starting in 1974 she courageously travelled around Spain, interviewing fellow former political prisoners about their terrible experiences so that these would not be lost. These interviews were recorded on a cassette recorder (for the benefit of any readers who are milennials, it would have been something like this ) and they later formed the basis of her bookCárcel de mujeres (1939- 1945)published in 1985, with a frontcover designed by Josep Guinovart. This has been published in English as Prison of Women: Testimonies of War and Resistance in Spain, 1939-1975 (State University of New York Press, 1998). A fully revised edition was later published in three volumes as Testimonios de mujeres en las cárceles franquistas (Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses, 2004) and one part was also published under the title Presas (Icaria Editorial, 2005). For a posting by Innovation and Human Rights which discusses her experience in the women’s prison of Les Corts in Barcelona follow this link . A budget has finally been approved by Barcelona City Council to establish a memorial on the site where the Les Corts prison used to stand.

- Ángeles Egido, a History doctorate, compiled bleak testimonies of the repressive conditions experience by women prisoners in her book El perdón de Franco. La represión de las mujeres en el Madrid de la posguerra (Catarata, 2009). On 8 March this year we included the data from her research in our centralised database and discussed her work in our blog entry Women Whose Death Sentences were Commuted. In her book Egido gives a detailed description of the commutation of the death sentences. Although commutation was supposedly a benevolent gesture, it was, in effect, a very cruel process. The death penalty was commuted in favour of a prison sentence of 30 years and one day. In some cases prisoners were not informed that their death sentences had been commuted and were forced, every evening, to listen to the announcement of the names of those who were to be executed the following dawn. The book also analyses the fundamental role of the Catholic Church in supporting the prison system. We discovered her book during a conference entitled Pasados Traumáticos: Historia y Memoria en la Sociedad Digital ,organised by HISMEDI in the Universidad Carlos III in Madrid. At this event Innovation and Human Rights presented our centralised database after it had been incorporated into the Entorno Virtual de Investigación del Laboratorio de Innovación en Humanidades (LINHD) de la UNED. You can see all the videos of the conference by following the link here.

The following volumes, dealing with memories of the Civil War and the Postwar period and written by women, are, in some cases biographical; in other cases they are works of fiction. Both approaches are equally valid in providing a view of the reality of the period, from the point of view of women protagonists.

- Carlota O’Neill was the author of the first chronicle of the outbreak of the Civil War (Primera crónica del estallido de la Guerra Civil) . She was a Republican intellectual whose father was a Mexican diplomat and whose mother was a Spanish writer and pianist. When the military rebellion occurred in July 1936 O’Neill was on holiday in Melilla along with her two daughters and was visiting her husband, Captain Virgilio Leret, who was acting head of the Atalayón Seaplane Base in the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco. Leret was executed on the first night of the attempted coup d’etat, although his wife was not informed until three months later, during which time she had spent a hellish period in prison. It would be years before she could recover custody of her children. Her autobiographical account of her experiences entitled Una mujer en la guerra de España (Ed. Oberon, 2004), was originally published in 1964 in Mexico, where she subsequently lived in exile, under the title Una mexicana en la guerra de España. An English edition, under the title Trapped in Spain was published in 1978 by Solidarity Books (Toronto, Canada). In the 1930s O’Neill had founded the feminist magazine Nosotras. Following her release from prison in 1940, during the harsh postwar years in Spain, she made a living as a writer using several different pseudonyms, before leaving for Venezuela and Mexico. For more information on her and a video follow this link .

- Constancia de la Mora wrote her autobiography Doble esplendor (Ed. Gadir, 2004) in the United States within months of the end of the Civil War and it was first published in English in 1939 under the title In Place of Splendour. She was the grand-daughter of Antonio Maura, who was Prime Minister of Spain on four occasions during the reign of King Alfonso XIII. Her uncle, Miguel Maura, was Minister of the Interior in the first government of the Republic. In her book she recounts her childhood experiences in a privileged family, her stay at a private school in Cambridge (UK), and how her concern over social conditions in Spain led her to support the Republic from 1931 onwards. Like O’Neill she was also married to an airman, Ignacio Hidalgo de Cisneros, who was her second husband (Her first husband was the brother of Luis Bolín, who became Franco’s press chief and whom she divorced immediately after the legalisation of divorce in 1933.) During the Civil War, while Cisneros rose to become Head of the Republican Airforce, she worked initially as the head of a home for refugee children and later in the Republican Foreign Press Office, of which she became Head in November 1937. She was based in several different cities in the Republican zone, and, shortly before the defeat of the Republic she left Spain to promote the Republican cause in the United States, convinced that she would soon return. The prologue to the Spanish edition of her book was written by her first cousin Jorge Semprún.

- Elena Fortún was the pen name of María de la Encarnación Gertrudis Jacoba Aragoneses y de Urquijo, who, during the Franco period, was the author of a series of very successful children’s books, which featured a character called Celia who was a very critical and inquisitive child. This same innocence and capacity for critical thinking occur in Celia en la Revolución (Ed. Renacimiento, 2016), in which Fortún presents a fictional account of Republican Madrid during the Civil War, seen through the eyes of the adolescent who had been Celia. What is surprising is that, although this novel is set in Civil War Madrid, the Madrid of “No Pasarán” (“They shall not pass”), it could have been an account of life in many other cities during the conflict with its portrayal of the harshness of day to day life, in terms of death, hunger, uncertainty, shortages of everything and fear, all presented without expressing an opinion. There was a first edition (1987) but, according to Andrés Trapiello in the prologue to the 2016 edition, “barely had it been published, than it disappeared from bookshops, since when it has only surfaced in the rare books market, appearing one copy at a time, always at fabulous prices.” The story of how this book came to us is in itself a wonder: the manuscript, written in pencil, was recovered in the 1980s (long after the author’s death in 1952) by Marisol Dorao (PhD in Philology, University of Cádiz), who travelled to the United States to obtain it from the daughter-in-law of the author. In 1993 Televisión Española created a series based on the books called Celia without including this volume. Editorial Renacimiento is publishing a new edition of the works of Elena Fortún, which have been out of print for many years, while the episodes from the TVE series Celia can be seen free by following this link.