Some Detailed Cases of Women in Catalonia

In 2017, the Parliament of Catalonia passed a law which annulled all of the sentences imposed by the military tribunals of the Franco Regime. As a result, the National Archive of Catalonia issued the llista de reparació jurídica de les víctimes del franquisme, which includes cases dealt with by summary military proceedings from 1937 onwards. 5,502 out of the almost 70,000 summary military proceedings in that list were opened to women. It amounts to eight percent of the total.

Summary military proceedings, usually known as “court martials” (sumarísimos), were part of military justice and, after the war, all justice was military justice (What were the summary military proceedings?)

In 1939, at the end of the Civil War, anybody who was denounced

as having been a member of a political party or a supporter of the Republic could find themselves facing a firing squad. A few insubstantial and unverified allegations related to the crime of “rebellion” could lead to the opening of summary military proceedings leading to a sentence within weeks.

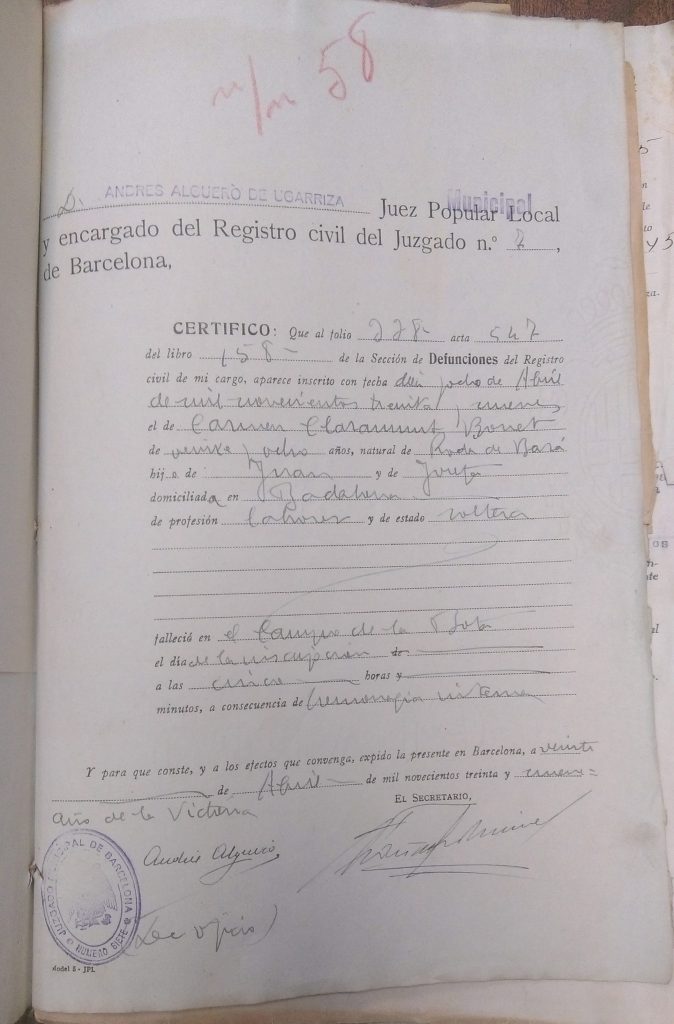

This was Carme Claramunt‘s sad fate. She was the first woman to be executed by a firing squad at the Campo de la Bota in Barcelona. Claramunt, aged 41, was a single housewife who had been born in Roda de Barà in the province of Tarragona. She lived in Badalona, near Barcelona, where she worked in a shop which sold fashion accessories. Angelina Picas, who ran the shop and who was called “auntie” by Carme, was childless and wanted to leave the shop to her. Claramunt was tried on charges of having denounced and thus caused the deaths of several right-wing people during the Republic. According to the work of the historian Emili Ferrando in his book Executada, some of the accusations against her were made by the nephews and nieces of Angelina Picas, who wanted to inherit the shop.

The victorious leaders of the military rebellion occupied Barcelona on 26 January 1939 and quickly established tribunals which could carry out summary trials within a matter of hours. On 2 March Carmen Claramunt, after being “arrested by members of the Falange Española,” was put into preventive custody. Within a week five of her neighbours had testified.

The summary of her case includes two statements: one from the Falange and the other, written in a similar style, from the Civil Guard (Guardia Civil). There is also a summary of the indictment describing her as “Dangerous extremist. Enemy of the nationalist regime.”

According to the prison records for 1939, cited by Fernando Hernández Holgado in his doctoral thesis “La prisión militante”, Carmen Claramunt pleaded not-guilty to all of the charges and was sent to the Corts de Barcelona women’s prison on 13 March. On 27 March her case went before a consejo de guerra sumarísimo (summary military court) accused of the offence of “military rebellion.” Later the same day she was sentenced in a joint hearing along with seven other people. Along with one of the men she was sentenced to death. (For further details see case summary No 58 in the Archivo del Tribunal Militar Territorial Tercero de Barcelona).

The record contains two errors: her second surname is given as ‘Bonet’ instead of Barot and her age is given as 28 instead of 41 as stated by Ferrando.

However, executions could not be carried out without being expressly authorised by the Generalísimo from his Headquarters and this authorisation (known as an “enterado”) was not received by the prison until 17 April . Claramunt would have known her sentence but she would not have known her fate until she was informed that the death sentence was to be carried out the next morning. By then she had spent over a month in the women’s prison of Les Corts. A few hours before being executed she said goodbye to her “auntie” in a letter which Ferrando reproduces and transcribes in his book: “you already know that they are killing an innocent person (…) my only regret is to leave you but be assured that God wants this; from heaven I will ask that you will not lack anything”. Carme Claramunt was executed by firing squad at five in the morning on 18 April 1939, only five weeks after her arrest.

The same month two other women came to the same sad end: Elisa Cardona Ollé, in Tarragona, on 22 April and Encarnación Llorens Pérez, in Barcelona, on 26 April. In total, 17 women were executed in Catalunya after the Civil War. We now have more information about the others.

The Repression against Women: Some Statistical Data

The repression carried out by the military authorities by means of summary proceedings was at its most intense immediately after the end of the Civil War: 86% of the total of 3,362 executions were carried out in 1939.

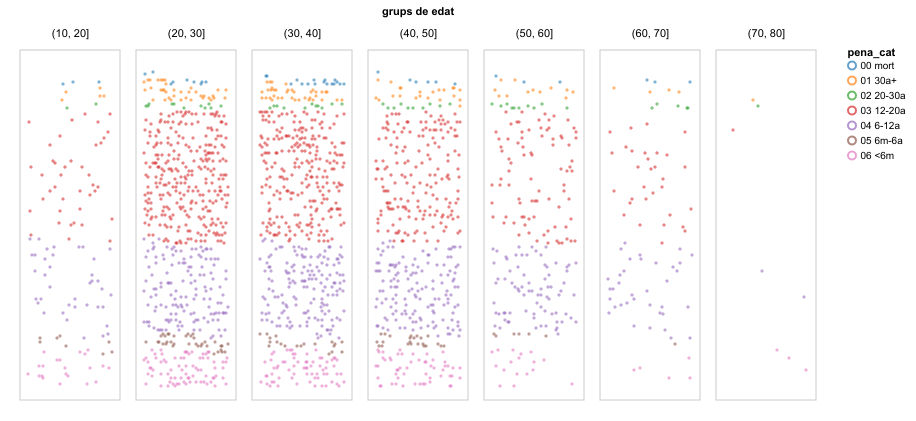

Of the nearly 70,000 cases handled by summary military proceedings 5,502 cases were brought against women, which amounts to nearly eight per cent of the total.

Analysis carried out by Innovation and Human Rights of the data on all of the women included in this list of victims of the Francoist summary judicial system allows us, for the first time, to consider the summary military proceedings from the point of view of gender.

Three of every four of the 5,319 women tried by the Military Authorities up to 1978 were tried during 1939. All of the seventeen women executed by firing squad on the orders of the courts were shot during 1939. Another 24 women were condemned to death; however, they were not executed.

In one case – that of Carmen Lopez Cano – three different sets of military judicial proceedings were opened in 1939. In addition there are 181 cases of women for whom two separate proceedings were opened.

In 40% of the cases, following early investigations, the women were not detained or were subsequently released; but they acquired the stigma of having been investigated and had often suffered a period of imprisonment. For the others, the most common sentence was one of imprisonment for between twelve and twenty years. The second most common sentence was of between six and twelve years imprisonment. For details follow this link.

Minors, the Elderly and the Waiting

In 1939 alone a total of 795 women were condemned to between 12 and 20 years in prison. Even those who were, in legal terms, still minors, were subject to the repression. Until 1972 the age of majority was 21 years, but, under Article 321 of the Civil Code, all women under the age of 25 were prohibited from living outside their family without parental consent, unless it was to get married or enter a convent. Once they had married, all women were obliged to present what was called the “marital license” in order to work, to carry out a trade, to occupy a public office or to obtain a passport.

Nevertheless, during the postwar period, 6 fourteen year old girls and 5 fifteen year old girls were charged. Between 1939 and 1975, 87 girls under the age of eighteen and 466 women aged between eighteen and twenty-one were also charged. [see the data here]. Moreover, one legal minor, Eugenia Gonzalez Ramos, was even executed by firing squad at the age of twenty.

In 1939 also, one of the two youngest women to be found guilty, Encarnación Cano Cano, who was aged 16, was given a ten-year sentence. She had to wait four years for the sentence to be given because of the delays in the system.

People awaiting sentences were detained in prison. In the case of Barcelona this was in the prisión de Les Corts, which continued to function as a prison until 1955. The site of the prison is now occupied by the branch of El Corte Inglés on the Diagonal; the location is currently only marked by a sad-looking plaque. It was in Les Corts that the other woman tried in the same summary proceedings as Carme Claramunt, namely Teresa Vila Castellví, a 57 year old widow who had been condemned to 15 years imprisonment, died two weeks after the execution of Claramunt, on 5 May 1939.

Her case, however, does not end there, and, as presodelescorts.org comments “Some idea of the efficiency of the judicial-penitential system of the regime is indicated by the fact that in 1944 her prison sentence was to be commuted from one of fifteen years to one of five, without the corresponding military court being aware of her death” which had occurred five years before. Only the archives now provide a record of such deaths of people held in prison.

The other sixteen-year old girl sentenced was Maria Angustias Mateos Fernández [see the data here], who received a five year prison-sentence in 1973. She was tried on terrorism charges along with her partner Jose Luis Pons Llobet in the same military trial as Salvador Puig Antich. Both Mateos and Pons were pardoned in 1977.

Charges were also brought against elderly women, including eleven who were over the age of 75 years [see data here]. The eldest of these was Antonia Castán Viu, who in 1938 received a sentence of 39 years imprisonment when she was already aged 79! This was later reduced to twelve years.

The five longest running military judicial proceedings were only finally closed after between 27 and 32 years. [see data here]. Finally one curiosity may be of interest: the most common first names of the women charged were as follows: Maria, Teresa, Carmen, Dolores y Josefa, in that order [data here].

The analysis of the data of all of the women included in the reparation list for the victims of the Franco Regime, drawn up by Innovation and Human Rights, enables us to analyse the outcomes of the summary military courts for the first time from the point of view of gender. This analysis has been possible thanks to the Law to Annul the Trials of the Franco Regime of 2017 and to the fact that, following its passage, the Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya published the database of the summary trials in a reusable format, which itself is the result of ten years work on the documents in the Archive of the Tribunal Militar Tercero.

Read on our website what the sumarísimos were and find out how many records we have included in our database so far.

A jupyter notebook produced by Innovation and Human Rights complements this Investigation of the summary military trials: Some Detailed Cases of Women in Catalonia. This provides access to the open source code and to the raw data which we have used to provide this information.

Grateful thanks are owed to Martin Virtel, Professor of Journalism BCN_NY, founder of the data consultancy Datenfreunde and member of dpa-Newslab, the innovation unit of Deutsche Presse Agentur, the German press agency.

[Translation by Charlie Nurse]

Photo: Militiawomen, 1936. Author: Gerda Taro. Public domain.