Sixty years ago, in April-May 1962, a strike in the coalfields of Asturias which spread to other sectors of the Spanish economy presented the biggest challenge to the Franco Dictatorship since the end of the Civil War. Often known as La Huelga del Silencio due to its peaceful and non-violent character, the strike led to the imposition of a State of Emergency (estado de excepción) in the provinces of Asturias, Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia and challenged the regime’s ability to control the working class through the Organización Sindical Española (O.S.E.), the state-run organisation established at the end of the Civil War.

The Asturian miners’ strike of 1962 can be seen as the harbinger of the industrial action which would mark the final years of the Dictatorship. To mark 1st May, International Workers Day, we are publishing this post to highlight the importance of the struggle of the Asturian miners and their families as well as those workers in other parts of Spain who risked their livelihoods and their lives by confronting the repressive labour policies of the Franco Regime.

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, the Asturian miners –famous for their resistance in October 1934 – were not a major source of opposition to the dictatorship. Asturias had been the last of the northern coastal provinces to fall to the Francoist armies in 1937 and the miners were subjected to fierce repression. According to Ruben Vega, the leading historian of the Asturian labour movement, 410 miners were executed following Francoist consejos de guerra (courts martial) and at least 368 were murdered extra-judicially. (Ruben Vega García et al, El Movimiento Obrero en Asturias Durante el Franquismo, 1937-1977, p. 54.) [More information about consejos de guerra here]

Although mine-workers were exempted from military service after the war, mining was not an attractive occupation: it was both extremely dangerous and very unhealthy. According to Vega, an average of 85 workers per year were killed in mining accidents in Asturias in the 1940s and 1950s (the total mining labour force in the province was 30,000 in 1950 and 49,000 in 1958). Miners also suffered from a high incidence of silicosis and other occupational diseases (Vega p. 55).

By the 1960s Asturias produced about seventy per cent of Spanish coal. The industry, centred around Langreo and Mieres, the main towns respectively in the valleys of the Nalón and Caudal rivers, dominated the local economy and society. Although the mines were owned by 72 different companies, seventeen of these dominated the industry, employing 93 per cent of the workers and producing 90 per cent of Asturian coal. Until the late 1950s coal-mining was sheltered from foreign competition by the Francoist policy of autarchy, but the 1959 Stabilisation Plan, which opened the Spanish economy to imports, provoked a severe crisis in the industry, as Asturian coal was forced to compete with cheaper imports.

In Asturias, as elsewhere in Spain, the Stabilisation Plan provoked an economic recession and inflation which reduced workers’ real wages. The atmosphere in the mining communities was also influenced by the return of miners who had emigrated to Western Europe, especially to Belgium and Luxembourg. Working abroad they had experienced not only better working and living conditions, but had witnessed the freedom of workers to organise and to strike.

By contrast, in Spain strikes were illegal and until 1958 wage-rates had simply been imposed by government decree. Although the 1958 Law of Collective Agreements (Ley de Convenios Colectivos Sindicales) allowed collective bargaining at factory, local or national level, this had to be conducted within the structure of the O.S.E. and all agreements had to be approved by the Ministry of Labour. In 1960 a government decree ruled that strikes deemed to be politically-motivated or which were seen as representing a serious threat to public order constituted military rebellion and were subject to military jurisdiction.

Developments in the coalfields in the late 1950s should have alerted the Franco regime to increasing discontent. A strike at the La Camocha mine, near Gijón, in January 1957, in which the miners occupied the mine for nine days, resulted in improvements in conditions and wage rates. Another strike centred on the Nalón valley in March 1958 led to the declaration of a State of Emergency and the dismissal of 200 workers: miners of military age were conscripted and 32 workers accused of membership of the Spanish Communist Party (P.C.E.) received prison sentences of between two and twenty years (Vega p. 272).

The 1962 strikes began on 7 April at the Nicolasa mine in Mieres after a protest at harsh and brutal working conditions. Nicolasa was one of the larger mines employing 2,000 men and the strike spread quickly to other mines in the Caudal valley. By the third week of April miners in the Nalón valley had joined the action and the strikers demands now included freedom to organise and compensation for workers afflicted by silicosis. The government’s response was predictable: the arrest of mineworkers and, in some cases, their relatives, the torture of prisoners, the intimidating presence of the Policia Armada and the Guardia Civil in the streets of the mining towns and major cities. About 400 miners were detained and many others deported to other parts of the country. (Vega p. 282)

The struggle continued for two months and depended on the solidarity of the close-knit communities in the mining valleys. An important element of this was the role of women in smuggling leaflets to spread the strike and in encouraging solidarity with the miners cause. The company-run stores (economatos) were closed as soon as strikes broke out and families were forced to rely on small traders who provided credit and on Catholic church groups who organised communal kitchens (comedores).

Throughout April the repression was accompanied by a complete media silence. Despite this solidarity strikes spread to workers outside the mining valleys – to the mines of Leon, to the Río Tinto mines in Huelva, to the steel and engineering plants in Asturias and to the major engineering works in the valley of the Río Nervion around Bilbao. The declaration of a State of Emergency in the provinces of Asturias, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa on 4th May to deal with what were described as anormalidades laborales (“labour abnormalities”) had little effect. By the second half of May about 300,000 workers were on strike across the country, affecting factories in a total of 28 provinces, including Barcelona where production had halted at most of the engineering and textile factories in the province.

Meanwhile, on 6th May, a manifesto signed by 171 leading Spanish intellectuals – including Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Josep Fontana, Juan & Luis Goytisolo, Jose Bergamín, Salvador Espriu and Alfonso Sastre – called for the establishment of freedom of information and the right of workers to strike. [Read the manifesto here, archived by the Fundación Juan Muñiz Zapico]

Extraordinarily, the regime was forced to negotiate with the miners’ leaders: on 15th May a government minister, Jose Solís Ruiz, who, as Secretary-General of the Movement, was responsible for the O.S.E., travelled to Gijón for talks with a hastily assembled committee of miners’ representatives. This marked the only occasion during the Franco regime when the government was forced to negotiate directly with workers’ leaders. The building workers of Gijón greeted Solís’s arrival by joining the strike.

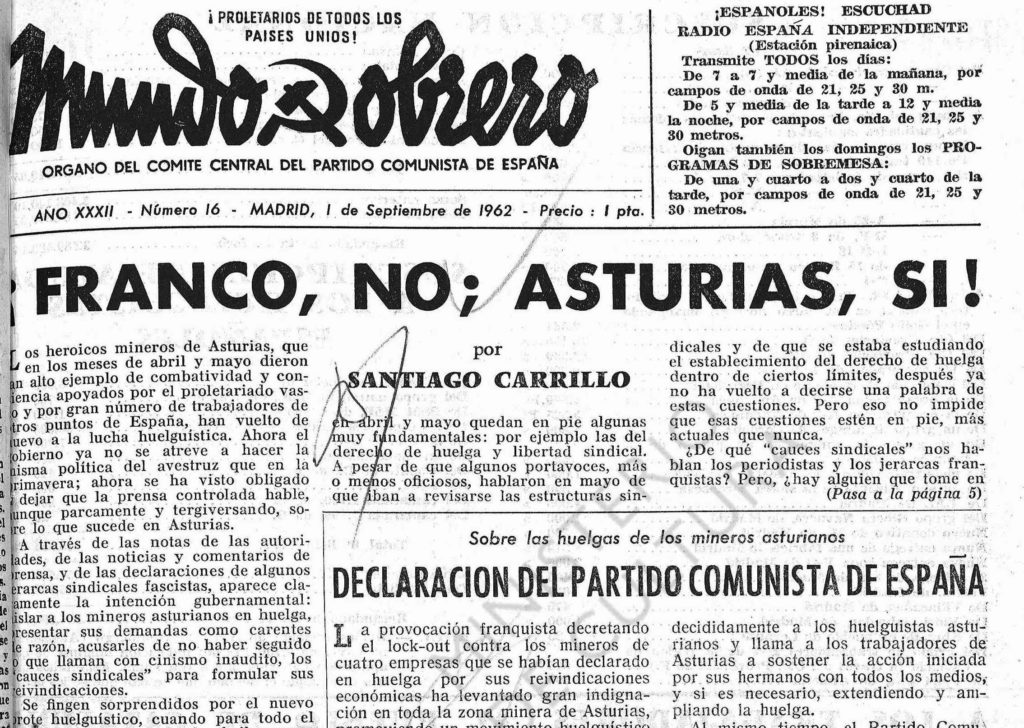

Even after Solís had conceded an agreement on increased wages and improvement in working conditions which was published in the Boletín Oficial del Estado on 24th May, the strike continued until detained miners were released and deported workers were allowed to return to the province. By then other groups had joined the protests: in late May there were student protests in Madrid and Barcelona. Demonstrators chanted “Franco No! Asturias Si!” and sang songs such as Hay una luz en Asturias que ilumina todo España (“There is a light in Asturias which lights up the whole of Spain”) and Asturias patria querida (“Asturias my beloved homeland”). (Vega, pp 282-3)

The return to work of the miners between 4th and 7th June was followed by an end to the other strikes. However, there was, perhaps inevitably, a sequel to the Asturian strikes of April-May. In August a second round of strikes broke out over the victimisation of some miners and the failure to fully implement the agreements which ended the earlier dispute. Both the Caudal and Nalón valleys were quickly brought to a halt. This time, however, the police and employers had compiled a black-list of workers: 126 were deported to other provinces and many others were dismissed. The strikes soon collapsed, partly because many miners and their families did not have the resources to resist after the two-month stoppage earlier in the year. (Vega, pp. 282-90)

As was customary, the regime blamed the strikes on Communist activists particularly from other countries. On May 27th addressing the Hermandad de Alfereces Provisionales, an organisation of Falangist war veterans, at Mount Garabitas, a Civil War battlefield outside Madrid, Franco claimed that the Civil War was still being fought, dismissed the strikes as unimportant and attacked un-named enemies for exploiting the situation. A few months later he told the New York Times correspondent Benjamin Welles

Italian and other foreign agitators came into Spain equipped with funds, but they got away before our police could put their hands on them.

Benjamin Welles, Spain: The Gentle Anarchy, 1965 (p. 130)

While the initial dispute at La Nicolasa can be seen as improvised, members of various clandestine opposition groups played important roles in spreading the strike, both in Asturias and elsewhere. As well as the Spanish Communist Party (P.C.E.), these included activists from the Socialist U.G.T. (Union General de Trabajadores) and members of Church groups, especially from the Juventud Obrera Cristiana (J.O.C.) and the Hermandad Obrera de Acción Católica (H.O.A.C.). Police reports suggest that the government was particularly alarmed at the activities of Catholic activists. While the Bishop of Oviedo, Segundo García Sierra, was hostile to the strikes and transferred J.O.C. activists from the mining valleys to rural areas, police reports identified numerous priests, particularly in the Basque provinces, whose sermons indicated support for the strikers’ cause. (Vega, p. 285).

The events of April-May 1962 had, however, raised serious questions for the future of the Franco dictatorship. The regime had been humiliated: a government minister had been forced to travel to Gijón to negotiate directly with the miners’ leaders, even though, since strikes were illegal, the latter were – according to the laws of the regime itself – criminals. Publication of the agreement reached by Solís while the strikes continued was another humiliation. Clearly this indicated the failure of the Francoist system of manage labour relations through the usual methods of the state-controlled union and police repression. It also underlined the fact that, since strikes were illegal, any strike automatically became a political issue involving the government.

The spread of the strikes and protests during April despite the silence of the Spanish media and despite the heavily distorted coverage after the declaration of the State of Emergency raised questions about the effectiveness of the system of press censorship. This would be reformed in 1966 when Fraga Iribarne’s Press Law (Ley de Prensa e Imprenta) abolished censorship in advance but subjected the press to severe penalties for breaking the ill-defined rules on publication. The most important source of information about the strikes was Radio España Independiente, the Communist Party’s radio station based in Bucharest. Known by the public as “La Pirenaica”, its reports were listened to widely across the country. Analysis of police records by Ruben Vega indicates the accuracy of La Pirenaica’s reports, something which must have further alarmed the authorities (Vega, p 284).

The conflict in Asturias in particular and the strike wave in general severely damaged the Franco regime abroad at a time when it had been attempting to present an image of a conservative civilian administration governing a peaceful, modernising society. In February 1962 the Spanish government had officially requested the opening of negotiations for membership of the European Economic Community. The nature of the Franco regime meant this was probably never likely to succeed, but the events of April-May 1962 reminded governments and the public in Western Europe of the fascist origins of the Franco regime and the continuing repressive nature of the dictatorship. Demonstrations in solidarity with the miners erupted in Western European capitals and in the United States, while labour movements outside Spain drew attention to the lack of independent trade unions and the illegality of strike action.

These two documentaries will be of interest to readers who understand Spanish:

Listen to the song Hay una lumbre en Asturias, played by songwrite Chicho Sánchez Ferlosio.

It is part of the documentary Si me borrara el viento lo que yo canto [If the wind blew what I sing], by David Trueba in 1982 [Available here]

Mantenemos una base de datos con 1,4 millones de registros de la Guerra Civil y el franquismo. Suscribete a nuestro boletín de noticias aquí y considera la posibilidad de hacer una donación aquí. ¡Gracias!

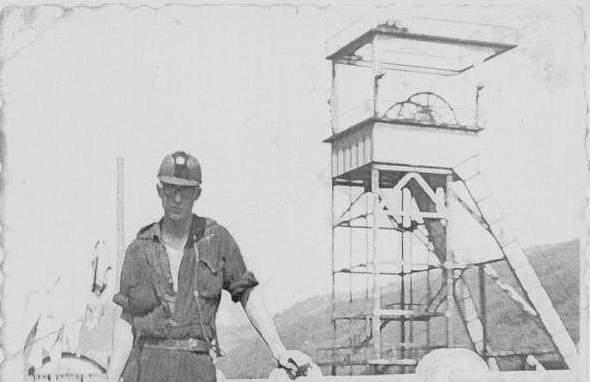

Photo: Miner in front of Pozo Nicolasa in 1967. Memoria Digital de Asturias CC-BY