The court martial of sixteen alleged members of ETA in Burgos in December 1970 provoked demonstrations and strikes in Spain and protests across Europe and elsewhere. These were used by the hardline Francoists of the so-called bunker to attack the “modernisers” of Opus Dei in the Spanish government and to pressure Franco for a return to the severe repression of the post-war years. The trial, in open sessions attended by foreign journalists, and the ensuing crisis also undermined the image the dictatorship had carefully nurtured abroad of a benevolent regime presiding over the modernisation of Spain. To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the trial, on 3 December 1970, we are publishing this account of the crisis and its significance in the history of the Franco Regime.

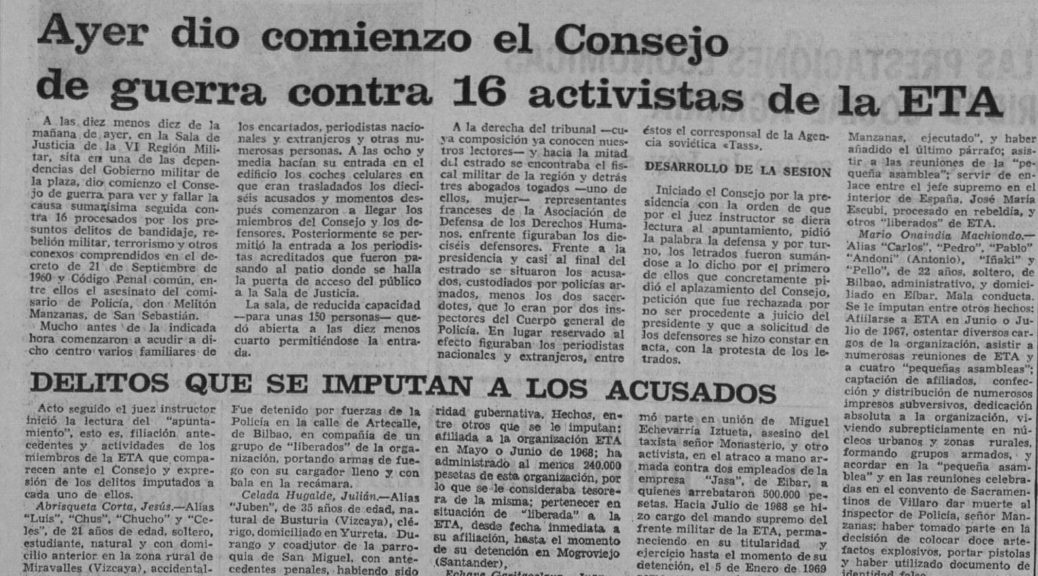

Although the origins of ETA can be traced to the early 1950s, it was only in the late 1960s that the group launched a series of violent attacks on targets in the Spanish Basque Provinces. In relation to the Burgos Trial the most important of these occurred in 1968. In June a Guardia Civil officer was killed in a shoot-out and in August Melitón Manzanas, the head of the San Sebastian Brigada Politico-Social (the regime’s political police force), was murdered on his doorstep in Irun. A State of Emergency (Estado de Excepción) was imposed in Guipuzkoa and police action across the Basque provinces led to the mass detention of suspects. Throughout 1969 and 1970 the accused were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment by courts martial in Burgos (the capital of the Sixth Military Region) for offences such as distributing ETA propaganda and attending illegal meetings.

During the 1960s the Franco regime had attempted to present an image abroad very different from its brutal origins in the Civil War and the post-war repression. Foreign journalists such as George Hills received the regime’s cooperation in presenting Franco as a benevolent family man. The US journalist Benjamin Welles, for example, reported Franco wearing “black and white sports shoes and a summer suit” when he interviewed him in July 1962 (Benjamin Welles, The Gentle Anarchy, 1965, p. 369).

The contrast with events in Burgos could not have been greater. In most countries courts martial were – and are – restricted to military personnel accused of military offences. In Spain, by contrast, martial law had been proclaimed by the military rebels in July 1936 and was not lifted until 1948. During and after the Civil War courts martial, often lasting a few minutes, issued heavy sentences including the death penalty, on thousands of people whose legal representation was performed by army officers [See Summary Military Proceedings]. Even after martial law ended, military courts continued in use for offences which in other countries would be dealt with by civil courts, particularly for those accused under the 1960 Decree on Military Rebellion, Banditry and Terrorism.

Tension rose in Spain ahead of the trial. On 22 November the Bishops of Bilbao and San Sebastian issued a joint pastoral letter declaring all violence illegitimate and calling for any death sentences imposed in the trial to be commuted. Strikes broke out across the Basque Country and elsewhere in Spain. On 30 November, in scenes unprecedented since the Civil War, protesters in Barcelona occupied Plaza Catalunya and fought police in the Ramblas. On the following day, the kidnapping by ETA of Eugen Beihl, the Honorary West German Consul in San Sebastian, attracted attention across Europe.

The week-long trial was attended by seven Spanish journalists, whose accounts closely supported the regime, and thirteen foreign correspondents. The sixteen defendants included two women and two priests. Their lawyers, who won the admiration of foreign correspondents for their courage, helped the defendants to advertise the goals of ETA and denounce police torture. The prosecution case focussed on the murder of Manzanas and was largely based on confessions extracted under torture. When questioning of the defendants began on the third day, they withdrew their confessions, gave graphic descriptions of their torture and denounced state repression of the Basques. This led to the next day’s hearing being suspended and when the trial resumed the defendants were prevented from making general statements or deviating from the questions. The reaction to this by the final defendant to be questioned, Mario Onaindia, was described by the French journalist Edouard de Blaye:

Shouting Gora Euskadi Askatuta (“Long live the Free Basque Country”), the prisoner leapt on to the platform and tried to grab an axe which lay among the ‘exhibits’ heaped on the floor. Alarmed, two of the magistrates drew their swords. One of the policemen raised his revolver and aimed it at the prisoner, but then lowered it for fear of hitting the judges. Onaindia, knocked over and pinioned, was quickly rendered helpless. Meanwhile, in the courtroom, uproar was at its height. The fifteen prisoners, chained together, plunged into an unequal struggle with the warders in charge of them. When they, too, had been overcome, they began to sing in chorus the old Basque anthem Euzko gudarik gera…From the public benches shouts arose: ‘Murderers! Long live ETA!’

Edouard de Blaye, Franco and the Politics of Spain, 1976, pp. 296-7.

The court was cleared and when the trial resumed in camera the proceedings were very brief. The defence lawyers refused to call the 25 witnesses whom they had planned to present. In his speech, the prosecutor called for death sentences on six of the accused and 752 years imprisonment.

For the next three weeks the seven judges considered their verdict behind closed doors. While Beihl was held hostage in a secret location in France and the prisoners awaited the verdicts, tension increased across Spain. On 12 December 300 leading Catalan cultural figures locked themselves inside the abbey at Montserrat and issued a protest manifesto before leaving on 14 December to prevent the abbey being stormed. The Vatican and several European governments called for clemency.

The Francoist hardliners also reacted. On 14 December, following a meeting of top army officers, a delegation of four Captains-General visited Franco at El Pardo to express the military’s concern at the situation. Hours later habeas corpus was suspended, allowing the indefinite detention of prisoners. Against a background of protest meetings across Europe, a large pro-Franco demonstration was organised in the Plaza de Oriente in Madrid on 16 December and rural labourers were bussed into the city for the event. On the following days similar pro-regime demonstrations occurred in other major cities. The spectacle of large crowds giving Fascist salutes and singing Cara el Sol (the Falangist anthem) – scenes reminiscent of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany – added to the shock felt across Western Europe. Film of the demonstration in Madrid was shown on the no-do newsreels to cinema audiences in Spain [see the no-do here].

On Christmas Day, with no decision from the judges, ETA released Eugen Biehl. Three days later the verdicts were finally announced. One of the sixteen defendants was acquitted, six were sentenced to death, three of them receiving two death sentences, and the remainder shared a total of over 500 years imprisonment. After a cabinet meeting two days later Franco announced his decision to commute the death sentences.

The crisis marked an important stage in what would prove to be the break-up of the Franco regime as, with an eye to the impending death of the dictator, the bunker rallied against supporters of “modernisation” of the regime. As Paul Preston has written,

The regime’s clumsiness had united the opposition as never before, the Church was deeply critical and the more progressive Francoists were beginning to abandon what they saw as a sinking ship.

Preston, Franco, 1993, p. 754

The trial was also a public relations disaster, reminding people and governments across Western Europe and in the Americas of the origins of the dictatorship and its continuing repressive and violent character. Follow these links for film of the demonstrations in London and Paris.

All fifteen prisoners were released under the 1977 Amnesty Law. Three of those sentenced to death would later play significant roles in Spanish politics. Between 1993 and 2000 Mario Onaindia represented Euskadiko Ezkerra in the Cortes after serving in the Basque parliament, where both Eduardo Uriarte and Jokin Goristidi served, Uriarte between 1980 and 1988 for Euskadiko Ezkerra and Goristidi between 1980 and 1994 for Herri Batasuna. In addition, Itziar Aizpurua, sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment, represented Herri Batasuna in the Basque parliament from 1982 to 1986 and 1994 to 1998 and in the Cortes between 1986 and 1993.

Three of the defence lawyers also enjoyed parliamentary careers after Franco’s death. Gregorio Peces Barba, a Socialist deputy between 1977 and 1986, was a member of the parliamentary commission which drafted the 1978 Constitution and President of the Cortes between 1982 and 1986. Juan María Bandrés represented Euskadiko Ezkerra as a senator between 1977 and 1979 and then in the Cortes between 1979 and 1989. Josep Solé Barberà served in the Cortes for the Communist Party between 1979 and 1982.

IMAGE: El Diario de Burgos. Biblioteca Digital de Castilla y León.