Seven years after the founding of ihr.world in 2016, our database has grown to include more than 1.4 million records of victims from the Civil War and the Franco Dictatorship. Now, after several months work, we are starting to add data on exiled Republicans. This article is intended to provide some necessary context: it is based on extracts from Informe sobre la Nacionalidad, by Ludivina García Arias, of the Asociación Descendientes del Exilio español published in 2004 por Equipo Nizkor in derechos.org. We are grateful for their kind permission to publish extracts from the report, which have been edited and slightly amended.

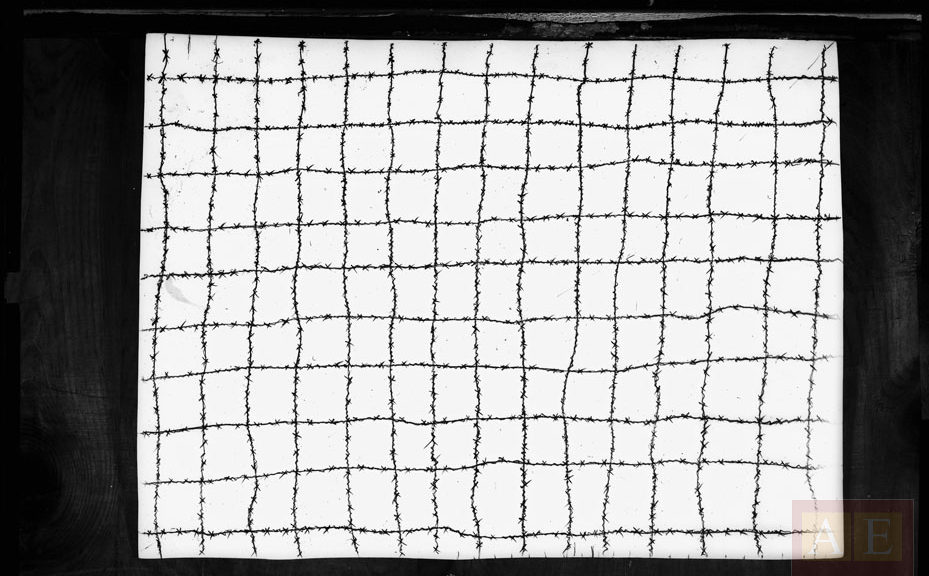

We have replaced the cover photo of our website (which showed a group of women in the cemetery in Lleida where they had gone to identify their relatives who had been killed in an aerial attack on the city on 3 November 1937) with another by the same photographer, Agustí Centelles, which shows a group of refugees in a concentration camp in the south of France. This photo, which is well-known, is, in fact, a compilation of two photos: the one that illustrates this article (a barbed wire fence) and the one that now appears on the front page of our website (a group of refugees). This is the well-known photo:

Introduction

In February 1939, after the fall of Barcelona to Franco’s armies, hundreds of thousands of Spanish people fled across the French border. The number of people involved in the Republican exodus has been subject to a wide variety of estimates. Some have put the number as high as one and a half million. It is almost impossible to establish a definite number as the figure was constantly changing due to some people being repatriated and others leaving France for other countries.

The Vallière Report, drawn up at the request of the French government, gave a figure of 440,000 refugees on 9 March 1939, of whom 170,000 were women, children and the elderly; 220,000 were soldiers or militiamen, 40,000 were invalids and 10,000 were wounded.

Approximately 275,000 Spaniards passed through French internment camps. By December 1939, more than 250,000 refugees had returned to Spain.

Those remaining in France, numbering approximately 200,000 people, can be seen as constituting the Spanish exiles from the war. A year later, according to the French Minister of the Interior, 167,000 refugees remained in France; to this figure we should be add those who had reached the Americas and those in North Africa.

Republican political and trade union leaders were involved in finding solutions to the problems of moving the exiles and providing for their care. Two organisations: the S.E.R.E. (Servicio de Emigración para Republicanos Españoles) and the J.A.R.E (Junta de Auxilio a los Refugiados Españoles) managed the refugee diaspora, especially to Latin America.

Under a French government decree of 12 April 1939 foreign refugees and stateless persons were required to provide compulsory service. The Spanish refugees were offered four options: to be recruited individually by agricultural or industrial employers; to join Foreign Workers Brigades; to enlist in the French Foreign Legion; or to join the Foreign Volunteer Battalions of the French army, which were military units under French command – after the outbreak of the Second World War. They would be contracted for the duration of the war.

Some 50,000 Spaniards were attached to the Workers’ Brigades, of whom about 12,000 were sent to help build the Maginot Line and about 30,000 to the area between the Maginot Line and the River Loire. A further 5,000 were members of regular Battalions of the French army. Those who remained in the camps were older men, the sick, invalids and the wounded and those considered dangerous because of their political activism.

World War II

After the invasion of Poland and the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 the living conditions of Spanish refugees became even worse, especially after the German invasion of France in May 1940 and its division into two zones in the following month.

The German occupation of France further increased the risk to the safety of asylum seekers who were exposed to kidnapping and extradition to Spain or to deportation to labour camps or extermination camps in Germany. In this situation, the Mexican government of Lázaro Cárdenas, in an admirable gesture of international solidarity, ordered its diplomats in France and a number of other countries to support Spanish refugees until the signing of a treaty for the protection of Spaniards in France.

From August 1940, the (highly restricted) rights of Spanish exiles in France depended [at least in theory] upon three documents: the Franco-Mexican Convention of August 1940, the French Law on the Extradition of Foreigners of 1927 and the Franco-Spanish Treaty of 1877.

The Mexican government and Republican political leaders had good reason for concern over this situation. In a letter sent by the German embassy to the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 20 August 1940, Franco’s government was asked whether it wanted to take charge of the 2,000 Spanish “reds” who were at that time interned in Angoulême.

In a second letter dated 28 August, the German embassy, in addition to referring again to the refugees in Angoulême, also raised the question of more than 100,000 “reds” in the camps in southern France and notified the Spanish authorities that, if they refused to accept them, the Nazis intended to deport them from France to other destinations. Two more notes, dated 13 September and 3 October 1940, written in identical terms, demonstrate that the Francoist government had abandoned the Spanish refugees.

On 13 September 1940, Ramón Serrano Suñer, who was Minister of the Interior [Gobernación] between 30 January 1938 and 15 October 1940, went to Germany and met Hitler carrying precise instructions from Franco to avoid any formal commitment to enter the war. Hitler requested a summit meeting between the two leaders.

After his visit the deportations of Republicans to Mauthausen and other death camps began. In the following months Lluis Companys, Joan Peiro, Julián Zugazagoitia, along with Manuel Azaña’s brother-in-law Cipriano Rivas Cheriff, were kidnapped in France and extradited to Spain. Companys, Peiró and Zugazagoitia were courtmartialed and shot by death squad. The death penalty on Rivas Cheriff was commuted to 30 years imprisonment. After his release in 1947 he left for Mexico.

The Nazi regime also forced 40,000 Spanish Republicans to join its labour battalions, while another 12,000 Spanish Republicans were deported to various concentration or extermination camps. [Note: their names are on our database here]

Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and Serrano Suñer, as well as Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo and General Franco held a meeting in mid-October 1940, at which it is believed that they discussed the issue of Spanish prisoners in concentration camps.

A document from Himmler, issued on behalf of Hitler, orders that some of the Republican exiles in France should be deported to concentration and extermination camps.

Serrano Suñer, who became Spanish Foreign Minister on 16 October 1940, refused to recognise the Spanish nationality of the Republican exiles, many of whom were exterminated in the Nazi camps, often after suffering all kinds of torture, ill-treatment and humiliation during their captivity. In Mauthausen, they were forced the wear a blue triangle identifiying them as apátridas (stateless).

By contrast, at the same time as the exiled Spanish Republicans were declared stateless by the Francoist government, Francoist embassies and consulates indicated the government’s willingness to grant Spanish citizenship to some Jews in Nazi-occupied countries. In a letter to the Spanish Embassy in Paris in 1940 Serrano Súñer advised ‘that the Sephardic Spanish subjects should clearly state their status as Spaniards in order to be defended as such at the appropriate time’.

The exiles in France

At the end of the Second World War, the situation of the Republican refugees in France varied enormously. Although many had become integrated into local communities, many others showed the after-effects of their exile and the war. In addition to the experiences of the surviving deportees and those wounded in the two wars, there were the problems caused by family separation, precarious living conditions and the illnesses which accumulated as a result of years of poor physical health. Moreover, the internment camps continued to be a reality for those who had no other alternative.

In the first months of 1945, the French government extended the legal status of Spanish refugees by providing them with the protection established for refugees before the Second World War. A decree of 15 March 1945 granted refugee status to those Spaniards who, de jure or de facto, did not enjoy protection from the Spanish government. They were thus able to benefit from international refugee status as established by the Convention Relating to the International Status of Refugees of 28 October 1933, i.e. they were able to enjoy the benefits of the Nansen status which, before the Second World War, had been granted to Russians, Armenians, Assyrians and other groups of refugees.

As a result Spanish refugees received an identification and travel card whose design was virtually identical to that of the Nansen passport, the name of which was officially abolished after the war, although it continued to exist in everyday administrative parlance. As a result refugees were free to find work and settle in an area of their choice. During the early post-war years, however, many refugees saw this as a temporary situation, as they had great hopes of soon being able to return to Spain.

By decree of 3 July 1945, a Central Office for Spanish refugees – OCRE – was created to provide legal and administrative protection for them. The International Refugee Organisation (OIR), was responsible for the office. In France, responsibility for the OCRE was shared between the Ministries of Justice, Foreign Affairs and the Interior. In effect, however, following the publication of decree, the French government asked the OIR to assume responsibility for Spanish refugees and urged it to represent them legally and administratively. The management of the OCRE was assumed by Spanish diplomatic or consular personnel who had previously worked in France and who had been domiciled in the country, uninterruptedly, since 1932 [i. e. before the Civil War].

Shortly after the creation of the OCRE, its managers went to the French departments where there were large numbers of Spanish residents and carried out an assessment of the post-war situation of the refugees. At the end of August 1945, the director of the OCRE, Fernando G. Arnao, submitted to Governor V. Valentin-Smith the results of this survey carried out in the prefecture delegations and the office’s delegations in the regions.

The OIR made some funds available to its organisation in France to provide, with the help of various charitable organisations, assistance to Spanish Republican refugees in France. Between September 1945 and the beginning of July 1946, the Service Social d’Aide aux Émigrants [Social Service for Assistance to Emigrants ] distributed a third of these funds, another third was distributed by the Quakers, and the rest by various other organisations including the Unitarian Service Committee and the American Christian Committee. The requirements stipulated ‘To be assisted, all Spanish refugees must provide the number of their certificate of nationality issued by the OCRE and authenticated by (the OIR)’.

Meanwhile, assistance to the wounded from the Spanish civil war – as well as to pensioners – was the responsibility of the exiled Republican government, then in Mexico.

At the end of 1945, there were also around 10,000 refugees in North Africa, 80 percent of whom were men, all of whom were registered with the Amicale d’Entraide for Spanish Refugees. Permanent assistance was needed for 180 people.

In December 1945, the Spanish Republican Government moved to France. Although France did not officially recognise the Republic, in February 1946, it granted the Republican Government a Statute recognising its right to organise, protect and represent those Spaniards living in France and its African territories who presented themselves voluntarily at one of its delegations, where they would be provided with documentation, visas, passports, nationality cards, etc., valid in the eyes of the French authorities.

In the early post-war years, however, many refugees refrained from applying for naturalisation as they expected the restoration of democracy in Spain. The proportion of those who wished to become naturalised or were in the process of naturalisation during the five-year period 1945-1950 was under 10% of the total of refugees, and consisted mainly of skilled industrial workers or specialised workers in the agricultural sector.

We recommend that readers who are interested should read the 2004 Nizkor Report itself, the full title of which is La cuestión de la impunidad en España y los crímenes franquistas. The Report was warmly received and its findings were widely endorsed, including by the renowned forensic anthropologist Francisco Etxeberria Gabilondo of the Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi.

It is important to stress the failure of Spanish governments to take action in relation to the Republican refugees. The case of the refugees is not, however, unique. As the recent report by Gregorio D. Dionis entitled Inanidad (2021) makes clear, no Spanish government since the restoration of democracy has taken any serious steps to provide justice to the victims of the Franco Dictatorship.

The Nizkor Report proposed an Action Plan which included the following two points:

10. The compilation of lists of Spanish victims of the Franco Regime in third countries, especially the so-called “children of the war”. It suggested that, where necessary, international cooperation should be requested, especially at the European level. For this purpose organisations of exiles or foreign organisations which were working with Republican exiles should be involved. In addition it also pointed to the importance of addressing the issues of Spanish nationality arising as a result of exile as well as those deriving from the registration of Spaniards under the legitimate authorities of the Second Republic and ensuring the maintenance of dual nationality to exiles and their descendants.

11. The compilation of lists of the victims of repression since the Francoist uprising in July 1936, in a manner which is legally valid, granting valid legal recognition and paying particular attention to legal minors, orphans and women.

In 2018 we took part in the Round Table event Pasados traumáticos. Historia y Memoria colectiva en la Sociedad Digital, along with Gregorio D. Dionis, whose report is mentioned above. You can watch the video of the round table here.

Photo: Alambrada. Reproduced under licence. SPAIN. MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE, Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, ARCHIVO CENTELLES, FOTO 1039.

Article translated from the Spanish by Charlie Nurse.