Last year, to mark International Women’s Day (8 March) and International Open Data Day (5 March) we published a virtual exhibition on Women who were subjected to trial under the Summary Military Tribunals established by the Franco Regime (Summary Military Proceedings Against Women) aand we added the dataset Mujeres asesinadas en Aragón: Eva en los infiernos to our database.

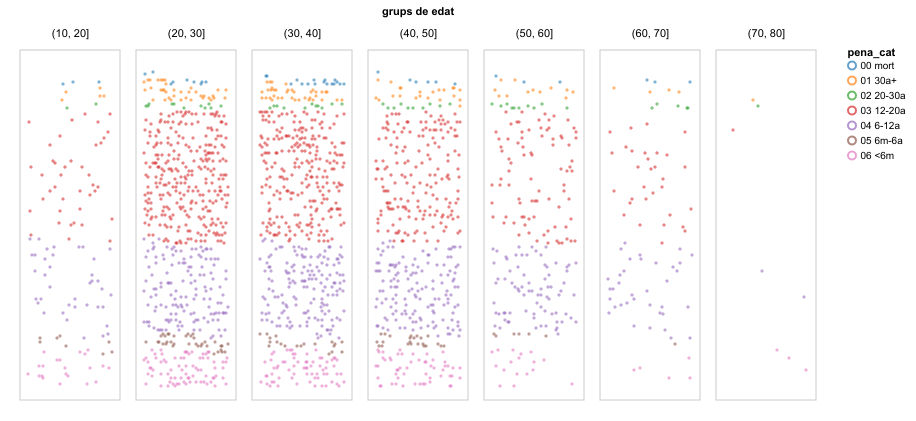

Thanks to the efforts of our team our database now includes over 570.000 personal files. Of those, 470.000 are from summary military tribunals (which are known in Spanish as sumarísimos) which were held in Catalunya , Madrid, la Comunidad Valenciana y Albacete. We can establish that, of the nearly 70,000 people subjected to these tribunals in Catalonia, 4,410 were sentenced to death and that 3,358 people were executed. Through archival work we have found the documentation dealing with the remaining cases, but the sentences imposed in each case have not been made public.

However, during the past year we have discovered a new piece in the puzzle of the map of victims and of those subject to reprisals during the Civil War: the Archivo General Militar de Guadalajara (General Military Archive of Guadalajara) has a 363-page list headed Los expedientes personales de penas de muerte conmutadas (personal files of those whose death sentences were commuted). This contains the names of people whose death sentences were not carried out because they were commuted to the sentence immediately below that of execution – 30 years imprisonment under maximum security – directly by the Head of State (Franco) himself, though often they themselves were not informed of this.

This means that we have now included three sets of data which relate to this other type of cruel repression carried out by the Franco dictatorship. Condemning someone to death when they were already in prison meant that on any night they might hear their name called out on the list of “sacas” or people who were to be executed the following dawn. There were some people who spent many months like this without knowing that their sentences had been commuted.

The three datasets which we are publishing include the names of:

- The 79 militiawomen whose death sentences were commuted (Milicianas con pena de muerte conmutada) which come from the doctoral thesis of Francisca Moya Alcañiz, Republicanas condenadas a muerte: analogías y diferencias territoriales y de género 1936-1945

- The more than 800 women whose death sentences were commuted (Condenadas a muerte con pena conmutada) which are taken from the book El perdón de Franco (2009), by Angeles Egido.

- The over 16,000 personal files of those people whose death sentences were commuted (Penas de muerte conmutadas), which are available as a result of the archive work by the Archivo General Militar de Guadalajara.

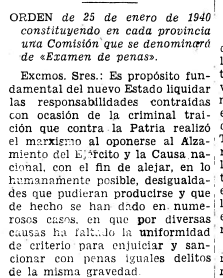

The

procedure for commuting sentences was as follows: names were proposed at

the provincial level by a provincial committee (Comisión Provincial de Examen

de Penas or CPEP) to a central commission (Comisión Central de Examen de Penas

or CCEP), which was subject to the

Ministry of the Army (Ministerio del Ejército).

The process of revising death penalties began in September 1942, over

two years after a similar process had begun for the revision of other sentences

which started in February 1940 with the establishment of the Provincial

Commissions to Examine Sentences (Comisiones Provinciales de Examen de Penas)

under the Orden de 25 de enero para constituir

comisiones provinciales .

In its prologue, this Order indicated recognition of the arbitrary nature of

the military judicial system by referring to the “lack of uniformity in the

criteria for judging and sentencing crimes of similar gravity”

Innovation & Human Rights is aware that in our database there are 79 cases of women whose names have been included three times and a further 832 cases where women’s names have been entered twice. We have done this in order to fulfill our objective which is to compile as much information as possible about every single one of the victims of the Civil War and of the Franco Regime. If someone finds their grandmother amongst these names, they will be able to obtain information about her from more than one source, even though, this will be, at least partly, based on the same documentary sources.

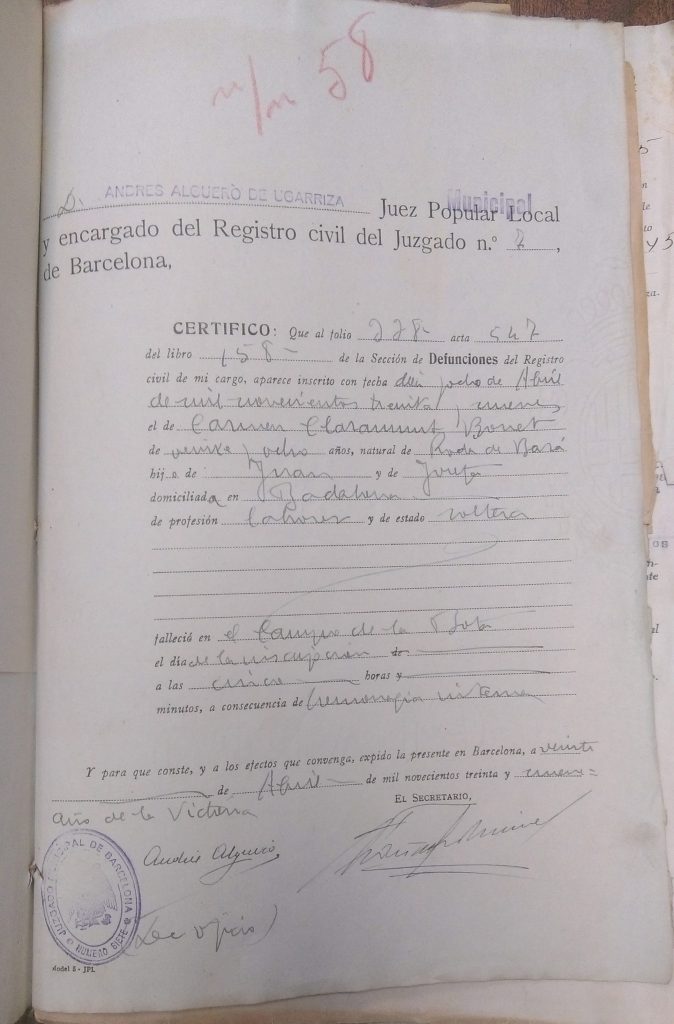

For example, the only militiawoman subjected to a court-martial in Catalonia and sentenced to death who is included in the Archivo Militar de Guadalajara as having had her death-sentence commuted is Adela Trilles Salvador. If we search for her in the database, we will find four references all of which are based on one documentary source. These references are to:

- Her court martial, in the llista de reparació jurídica de víctimes del franquisme, a list of people whose sentences by the Francoist military judicial system were cancelled under Llei 11/2017 of the Catalan Generalitat, published by the Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya, which may be consulted in the archives of the Tribunal Militar Territorial Tercero de Barcelona.

- The commutation of her death sentence in Penas de muerte conmutadas, a list published by the Archivo General Militar de Guadalajara.

- The book El perdón de Franco, by Angeles Egido on the repression of women during the post-war period which discusses detention, interrogation, torture and confinement in prison, as well as the “policy of supposed clemency the theoretical basis of which has its roots in redemption, following acceptance of guilt, and which is wrapped (…) in an ideological layer of pardon or amnesty, connected to religious ceremony.”

- The doctoral thesis Republicanas condenadas a muerte: analogías y diferencias territoriales y de género 1936-1945 by Francisca Moya Alcañiz. This lists 79 militiawomen which includes not only those who were physically at the battlefronts, but also those who, according to their sentences, dressed as militiawomen and carried weapons while they were actively participating in the Republican rearguard during the war.

For example, in the thesis, Adela Trilles is described as follows: “she was 33 years old, married, was a railway ticket-office clerk, was affiliated as a socialist, dressed as a militiawoman and was named head of the Juventudes Femeninas [the Socialist women’s youth movement], being condemned to death in Tarragona on 30 May 1939 as a propagandist and for having frisked women who looked suspicious in the station”.

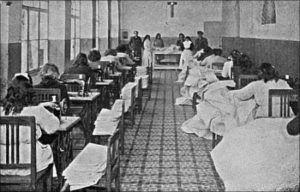

After being condemned to death and following the commutation of her sentence, Trilles was granted a conditional release from the Las Corts Women’s Prison in Barcelona in 1946, as listed in the Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), the official state gazette, on 6 March 1946 .

We are continuing to work on datasets and more will be included as soon as they are available.

Photo: Militiawomen CNT-FAI (public domain)