We have for the first time included data relating to some of the many people who became exiles as a result of the Civil War and the subsequent repression. Thanks to an agreement with the Fundación Pablo Iglesias, which has in PDF format the passenger list of the British merchant vessel Stanbrook which left Alicante at the very end of the civil war, we have been able to include details of these passengers in our database which now has 1,423,082 records, all of which are referenced to archives. Here is our description of this dataset.

Late in the evening of 28 March 1939 the Stanbrook, a British registered cargo steamer (1,383 tons) left Alicante carrying 2,638 passengers to exile. She was the last vessel to leave before Italian forces entered the harbour. Thousands of terrified refugees remained in the port and were taken off into hastily-established camps.

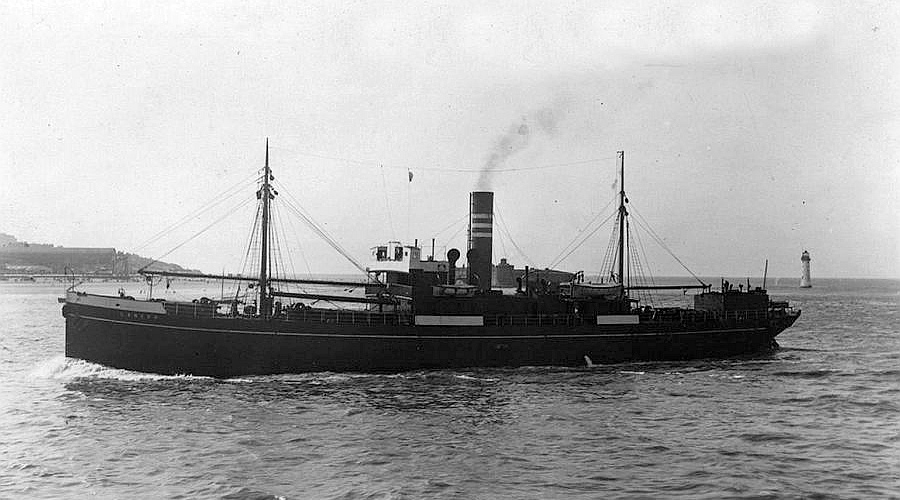

Built in a shipyard on the River Tyne in 1909 and originally registered as the Lancer, the Stanbrook was a very old vessel with a maximum speed of twelve knots and accommodation for 24 crew. In 1937 she was bought by the Stanhope company of London which had been established in 1934 by Jack Billmeir. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Billmeir’s fleet consisted of two vessels only, but he, like other British shipowners, spotted the opportunity presented of carrying goods to and from Republican Spain. Within a year the Stanhope company owned over twenty ships. Trading with the Spanish Republic was an increasingly hazardous business due to the activities of the rebel navy and airforce and those of its German and Italian allies. Shipping insurance for vessels trading with the Republic was expensive, especially for new vessels which were costly to replace. Along with other shipowners Billmeir bought up and re-registered old ships: almost all were given names which began with “Stan…” Patterns of trading were complex: vessels might, for example, transport goods to Spain, then sail to North Africa to pick up cargo for France, before sailing elsewhere or returning to Britain. Many of Billmeir’s ships made one voyage only to or from Spain and were then sold off, usually at a profit.

By March 1939 the Stanbrook had been carrying cargo to and from the Republic for about two years. This had not been without incident. In April 1937 the vessel was one of three ships to defy the rebel attempt to blockade Bilbao. The British journalist George Steer described their reception in Bilbao as they steamed up the Río Nervión accompanied by two armed Basque trawlers:

enormous crowds cheered as the procession of three red dusters [Red Ensigns flown by British merchant ships] passed slowly up river. They carried a cargo of 8,500 tons of food of which the most important element was 2,000 tons of wheat. Men in the patrol boat which preceded them up the Nervíon shouted ‘Pan! Pan!” and the women on the shore were mad with joy.

George Steer, The Tree of Guernica, 1938, pp. 207-8

In August 1938 the Stanbrook sank after being attacked twice by aircraft while lying at anchor at Vallcarca, south of Barcelona. The crew were safely evacuated but her cargo of cement was ruined. She was refloated a few days later and repaired. On February 9 1939 she was hit by shrapnel from an air raid while unloading foodstuffs in Valencia.

In March 1939 the Stanbrook’s captain, Archibald Dickson, was ordered to sail from Marseilles to Alicante to collect a cargo of oranges and saffron. Although she arrived in the harbour on 19 March, her cargo did not arrive until a week later. By then there were large numbers of refugees in the port, fleeing the advancing Francoist forces. The port authorities asked the captain to evacuate as many civilians as possible to Oran in the French colony of Algeria. In a letter written a few days later to the Sunday Dispatch, a popular British newspaper, Dickson described the refugees:

Amongst the refugees were a large number of women and young girls and children of all ages, even including some in arms. Owing to the large number of refugees, I was in a quandary as to my own position, as my instructions were not to take refugees unless they were in real need. However, after seeing the condition of the refugees, I decided from a humanitarian point of view to take them aboard as I anticipated that they would soon be landed at Oran.

Among the refugees were all classes of people, some of them appearing very poor indeed and looking half-starved and ill-clad and attired in a variety of clothing ranging from boiler-suits to old and ragged pieces of uniform.”

Dickson wrote that within ten minutes of leaving the port “a most terrific bombardment of the town and port was made and the flash of the explosions could be seen quite clearly from on board.” The voyage across the Mediterranean to Oran took 22 hours, sailing without lights to avoid attack from Francoist ships or aircraft. Since the British government had recognised the Franco regime on 27 February, the British navy was not prepared to intervene to protect the vessel. Dickson described conditions on the ship:

The number of refugees on board made it almost impossible to move on the vessel itself, as the hatches had been opened ready to load the cargo and consequently the refugees could only stand on deck.

On arrival in Oran the French authorities were reluctant to allow the refugees ashore: the women and children were allowed to disembark after a few days but the remainder were forced to wait several weeks. Most of the refugees were sent to Camp Morand near Boghari in the Sahara. The facilities at the camp were so poor that its closure was recommended at the International Conference for Assistance to Spanish Refugees, held in Paris on 15/16 July 1939, but this did not occur.

Three days after the departure of the Stanbrook Italian troops entered Alicante, followed by Franco’s forces. The fate of the thousands of people left behind in the port has been described by Paul Preston:

Families were violently separated and those who protested were beaten or shot. The women and children were transferred to Alicante, where they were kept for a month packed into a cinema with little food and without facilities for washing or changing their babies. The men – including boys from the age of twelve – were either taken to the bullring in Alicante or to a large field outside the town, the Campo de los Almendros, so called because it was an orchard of almond trees.

Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust, 2012, p. 480

Later in 1939, after the outbreak of the Second World War, the Stanbrook was sunk by a German submarine while sailing from Antwerp to Britain with a loss of all twenty members of her crew, including Archibald Dickson. In 2018 a plaque was unveiled to Dickson in his home city of Cardiff by Mark Drakeford, the First Minister of Wales and on 28 March 2019, the 80th anniversary of the Stanbrook’s evacuation, a bust of Dickson was unveiled in the port of Alicante. There is also a street in Alicante named after the vessel – “Calle Buque Stanbrook” .

More information about camp Morand here and about the Campo de los Almendros here (both in Spanish).

PHOTO: The Stanbrook in 1909, then sailing as the Lancer. Clive Ketley, Public domain, vía Wikimedia Commons