Just before midnight on 12 September 1923 Gen. Miguel Primo de Rivera, Captain-General of Catalonia, declared martial law and announced his seizure of power. On 15 September, after dismissing the existing government, King Alfonso XIII appointed Primo as Prime Minister. To mark the centenary of the 1923 coup we are publishing this blog post which focuses on the role of social conflict in Barcelona between 1919 and 1923 in preparing the road to the coup.

The parliamentary regime established in 1876 is often seen as having brought Spain political stability. However, from 1917, the regime entered a period of continuous crisis. In some respects the regime itself and the challenges it faced after 1917 may be compared with those of other West European countries in the period, such as Italy, the United Kingdom and Germany. Despite the adoption of universal male suffrage in 1890, Spanish politics was dominated by the landed and business classes. Their influence was exercised through pressure on the voters, particularly in rural areas, as well as through the existence of a nominated upper parliamentary chamber to check the elected lower chamber and through the continued power of the monarchy.

The immediate post-war years witnessed social and political conflict across Europe, partly as a result of the effects of the war itself and partly due to the post-war demobilisation of troops and attempts to restore the political and social order of the pre-war world. Additional instability was caused by the effects of the Russian Revolution: despite the shortage of reliable information on events in Russia, news of the Bolshevik seizure of power inspired many leftist groups across Europe and terrified members of the propertied classes. By 1917 the two aristocratic parties (Liberals and Conservatives) on which the system was based, were badly fractured, making it difficult to form a government with a stable majority in the Cortes and providing the opportunity for King Alfonso XIII to exercise greater political influence. Against this background the short-lived Spanish governments of the post-war period faced a series of challenges which would have tested any regime, among them the attempt to control the territory in Morocco allocated to Spain in the international agreements of 1904 and 1912.

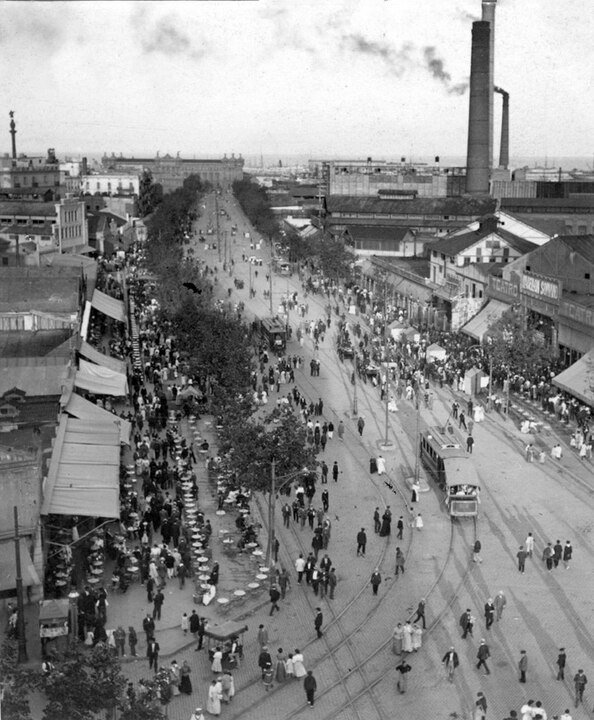

Though Spain had remained neutral, the effects of the First World War had been profound, disrupting the pre-war political structure, generating an economic boom which saw vast profits made from exporting goods to the British and French, accompanied by high inflation which exacerbated the struggles of the urban and rural populations in conditions of rapid industrialisation. While this affected all sectors of Spanish society, this process was particularly marked in Barcelona, as Francisco J. Romero Salvadó points out:

During the war years, no other Spanish city experienced such a disparity between the wealthy few and the labouring masses. The industrial boom brought extraordinary profits to the textile barons, financiers and businessmen of Barcelona….At the same time, the hard-pressed working class endured long shifts in factories and, with low wages, could hardly afford the rising prices of staple products and rents.

The Foundations of Civil War: Revolution, Social Conflict and Reaction in Liberal Spain, 1916–1923. Routledge, 2008, p. 126

While the years 1919-1921 are known as the “Trienio Bolchevique” largely for the strikes and rural revolts in Andalucía – which were put down with great violence and which involved the deployment of 20,000 troops under General Manuel Barrera – the crisis of the post war years was centred, perhaps not surprisingly, in Barcelona. In Romero Salvadó’s words:

The largest metropolis in the country, with an unequal background of labour mobilisation, the Catalan capital appeared as the paradigm of all the contradictions and tensions of this modernising process: massive immigration, a widening gap between an entrennched bourgeoisie and a pauperised proletariat, strong nationalist feelings, a restless local garrison, and a widespread mistrust of the distant and unrepresentative central administration.

The Foundations of Civil War: Revolution, Social Conflict and Reaction in Liberal Spain, 1916–1923. Routledge, 2008, p. 139

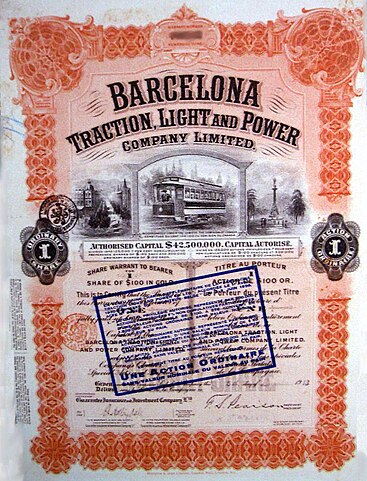

Of central importance in the city’s post-war experience was the great 44 day strike at the Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company Limited (known as La Canadiense or La Canadenca) between February and April 1919. Solidarity strikes by textile workers and utility workers plunged the city into darkness: trams stopped running and the shops closed. The strike demonstrated the power of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), the Anarcho-Syndicalist union federation which was able to enforce compliance with the stoppage. In conditions of little violence, the federation was able to rally support for the strike to the point where the printers union was able to block the publication of a decree from the Captain-General, Gen. Milans del Bosch, militarising the public services (the decree had the effect of conscripting workers who could then be prosecuted by courts martial).

Milans pressed the government to declare martial law, but the Prime Minister, Count Romanones refused and sought a compromise solution, which included the promise to introduce a maximum eight-hour working day (the first anywhere in Europe). Resolution of the conflict was, however, undermined by the resistance of many business leaders and by army officers stationed in the city, led by Milans himself. Arguing that drastic measures were needed to break the power of the CNT, they viewed the response of the Romanones government as weak and leaving them defenceless against a threat of revolution. They denounced the introduction of the eight-hour day as rewarding trouble-makers. Although Romanones had replaced the Civil Governor and the Head of Police with more conciliatory figures, these soon came into conflict with Milans and with the Military Governor, General Severiano Martinez Anido and were forced to catch the train to Madrid, a move which led to the resignation of the Prime Minister. This, as Romero Salvado argues, was a “coup in all but name” (The Foundations of Civil War, p. 198) and it received the enthusiastic support of the major institutions of the Catalan business class, notably the Fomento del Trabajo Nacional (FTN) and the Federación Patronal de Cataluña.

The Canadiense strike set the pattern for conflict over the next four years and can be seen as paving the route to the 1923 coup. Terrified by the power of the CNT, many of the big industrialists felt that they had been held to ransom during the Canadiense strike by a gang of criminals and were determined to reassert control over the labour force. As Romero Salvadó points out “in an age of mass politics and popular mobilisation, the old governing classes were increasingly perceived as unable to contain the revolutionary avalanche and defend the social order” (The Foundations of Civil War, p.191).

Even before the Canadiense strike the employers had begun to mobilise. Complaints of a lack of adequate policing were not new (with a population of 700,000 the city had only 1,000 officers) but in early 1919 business leaders and the army established a new parallel police force. This was given the old Catalan name of the Somatén, which referred to a medieval rural militia. Although the new force claimed to be an inter-class force of “patriotic citizens”, its leadership included figures such as Count Godó, the Marquis of Comillas and Francesc Cambó. Another, more shady force was also established with army support, by Manuel Bravo Portillo, a former police chief who had been dismissed for his role as a wartime German spy. This conducted a dirty war against CNT members, subjecting them to arrest, beatings and occasionally murder, often using information assembled in the so-called Fichero Lasarte, a card-index of members of the CNT which was assembled from underground sources. In October 1919, in an attempt to challenge the dominance of the CNT in the labour force, a new parallel union movement, known as the Sindicatos Libres was organised, again with army support.

In the period between the resignation of Romanones (April 1919) and September 1923 Spain was governed by eight different governments which attempted to grapple with the situation in the city. Some, such as those led by Antonio Maura (April-July 1919) backed the Barcelona elite and military leadership in their attempts to destroy the CNT. Maura’s successor, Joaquín Sánchez de Toca (July-December 1919) adopted a different approach, attempting to recognise the labour movement and bring it into the legal process, thus isolating the violent sections of the CNT. With 15,000 CNT members in prison, the new Civil Governor, Julio Amado, began negotiations with leading CNT figures and ended martial law. This was followed by a general amnesty, the implementation of the eight hour working-day and the introduction of a Comisión Mixta de Trabajo (a joint Employer-Labour Arbitration Committee).

After failing to persuade the government to support them in destroying the labour movement, the Catalan industrialists launched a partial lockout in November 1919. The Patronal denounced what it saw as the complicity of the government with the unions and called for “men of order” to seize power. (The Foundations of Civil War, p. 206). After temporarily lifting their lockout in mid-November, the employers threatened a complete lockout from 1 December unless the government closed down all the workers’ centres and arrested the union leaders. Faced with this, the Sánchez de Toca government collapsed a few days later. Despite the appointment of a new government and the hard-line Count Salvatierra as the new Civil Governor, the Catalan business groups were not satisfied: when Milans del Bosch was forced to resign in February 1920, a symbolic one-day closure of all businesses in Barcelona was called in protest and there were calls for the intervention of the king.

The alliance between the army leadership and the business classes played a major role in fuelling the violence for which Barcelona became notorious. Although violence spread from Barcelona to other industrial cities in Spain, it was at a much lower level. One contemporary writer listed a total of 225 deaths and 733 people wounded in violence in Barcelona in the years 1917-1921 (B. Martin, The Agony of Modernisation, 1990, citing J. M. Farré Morego, Las atentados sociales en España, 1922). Among the targets of anarchist gangs were industrialists and managers: in one spectacular attack on 5 January 1920 the car carrying the president of the Catalan branch of the Patronal, Felix Graupera was attacked, injuring Graupera and his driver and killing a police officer. The closure of all unions and the arrest of some 1,500 CNT members in early 1920, as well as the violent activities of police forces and the Somatén, increased the influence of the violent gangs within the anarchist movement and reduced that of syndicalist leaders such as Salvador Seguí and Angel Pestaña. Among the victims of anarchist violence were the prime minister (from May 1920) Eduardo Dato, assassinated by an anarchist hit-squad in Madrid in March 1921 and Count Salvatierra, the former Civil Governor of Barcelona, murdered in August 1920. Noticeably, the anti-labour squads did not restrict their targets to the violent parts of the anarchist movement: their victims included the charismatic and popular syndicalist leader Salvador Seguí (March 1923) and Angel Pestaña, who was wounded but survived assassination in August 1922.

After the resignation of Milans del Bosch, Catalan business leaders found a new hardline military champion in Gen. Martínez Anido, who became Civil Governor in November 1920, following pressure on the government. During the first three weeks of 1921 a total of twenty-one CNT members were killed under the application of the so-called Ley de fugas, the practice under which prisoners were shot and reported as having attempted to escape. To relieve congestion in the city prisons, manacled groups of prisoners were led out of Barcelona by mounted guards each week and forced to march to prisons across the country.

Although these policies weakened the labour movement, there was never unanimous support for these repressive policies among the parliamentary leaders in Madrid. The final two governments before the 1923 coup, led by José Sánchez Guerra (March-December 1922) and Manuel García Prieto who replaced him in December 1922, attempted a policy of “normalisation”, ending martial law, restoring civil liberties and attempting to introduce legislation on collective labour contracts. Meanwhile, Salvador Seguí and others attempted to rebuild the CNT and distance it from the violence of the anarchist gangs but his death led to a revival of terrorist activity by young gunmen such as Buenaventura Durruti. Their most spectacular attack was the murder of Cardinal Soldevilla of Zaragoza in June 1923. At the same time gunmen linked to the Sindicatos Libres and the police had resumed attacks on CNT members. Pestaña later noted that most of their targets were figures opposed to terrorism. As Romero Salvadó points out “Seguí, as the leader most capable of rebuilding the Anarcho-Syndicalist movement, was the person who had to be eliminated” (The Foundations of Civil War, p. 279).

The response of the FTN, the Patronal and the army leadership in Barcelona to the new approach of the Sánchez Guerra and García Prieto governments was predictable. In March 1923 the Catalan industrial leaders led a campaign to block the government’s attempt to introduce legislation on collective labour contracts (which would have provided a legal role for the labour movement). Following the dismissal of Martínez Anido as Civil Governor in November 1922, business groups began to look for a new defender, whom they found in the person of the newly-appointed Captain-General, Miguel Primo de Rivera.

Following a new transport strike in Barcelona in May 1923 which brought the city to a standstill, the FTN denounced the government for not only tolerating the situation but for protecting the CNT gangs and proclaimed Primo as their only possible saviour. On 12-13 September after Primo announced his coup in Barcelona he was accompanied and encouraged by many of the city’s key business leaders and his move was welcomed by the FTN and the Patronal. On his departure for Madrid to meet king Alfonso and be sworn in as Prime Minister, he was seen off by a reported 4,000 of the city’s prosperous citizens. Their support was not surprising: since 1919 they had, in alliance with military leaders such as Milans del Bosch and Martínez Anido, forced the resignation of two Spanish governments and resisted and undermined any government unwilling to pursue the repressive policies which they favoured. Along with their business allies in other parts of Spain, they had now abandoned the parliamentary regime established in 1876.

After the coup Milans del Bosch and Martinez Anido continued to play important roles in the politics of repression in Spain. Milans del Bosch served as Civil Governor of Barcelona between 1924 and the resignation of Primo de Rivera in January 1930. Martinez Anido was Minister of the Interior (Ministro de Gobernación) and Deputy Prime Minister (Vicepresidente del Consejo de Ministros) between 1924 and January 1930. Between January 1938 and his death in December 1938 he served as Minister of Public Order (Ministro de Orden Público) under Franco.

PHOTO: King Alfonso XIII (left) and Gen. Miguel Primo de Rivera, by unknown author. Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-09411 CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE. The image has been edited to fit the space.